From Pong to path tracing: The leaps that built modern game graphics

Graphics in games don’t improve in a steady, gentle slope. They jump. Someone ships a look that feels like it arrived from five years ahead, and then everyone else has to scramble to match it, optimise it, and make it affordable. That’s when a breakthrough becomes a leap, not when it appears in a lab demo, but when it shows up in games ordinary people actually play. In more recent times, it’s becoming difficult to discern what the “leap” really is since visual fidelity is at an all-time high and each leap isn’t purely giving improving fidelity but are also focused on optimising for the hardware. You’ll see how this is true later on.

Survey

SurveyOne quick note before we start, because it’s tradition at this point. Some folks might not find certain leapthroughs in this list, and that’s fine. The medium is old enough to support multiple canons, plus a few spicy comment sections.

We’re focused on explaining why each leap mattered in their era, not just because “it looked nicer”. These are the moments that “changed what games could be”.

A quick way to “see” graphics progress

Before we go decade by decade, it helps to have a mental model for why graphics progress sometimes feels dramatic, and sometimes feels like incremental polish. Most of the time, the same three forces are pulling at each other.

First, there’s what the hardware can do, meaning how quickly it can draw images and how complex those images can be. Second, there’s what developers can actually build in a sane amount of time. A feature can be technically possible and still be a non-starter if it adds months of work per level or requires a team of specialists most studios don’t have. Third, there’s what players notice. Some breakthroughs are under-the-hood and only become obvious when you compare games years apart. Others are instantly visible, even to someone who doesn’t care about technology, like reflections that suddenly behave “correctly” or lighting that suddenly feels natural.

When a leap sticks, it usually happens because those three forces line up. Hardware makes it possible, tools make it practical, and players immediately understand why it’s better. With that in mind, let’s start at the beginning.

Enter Pong – The first of its kind

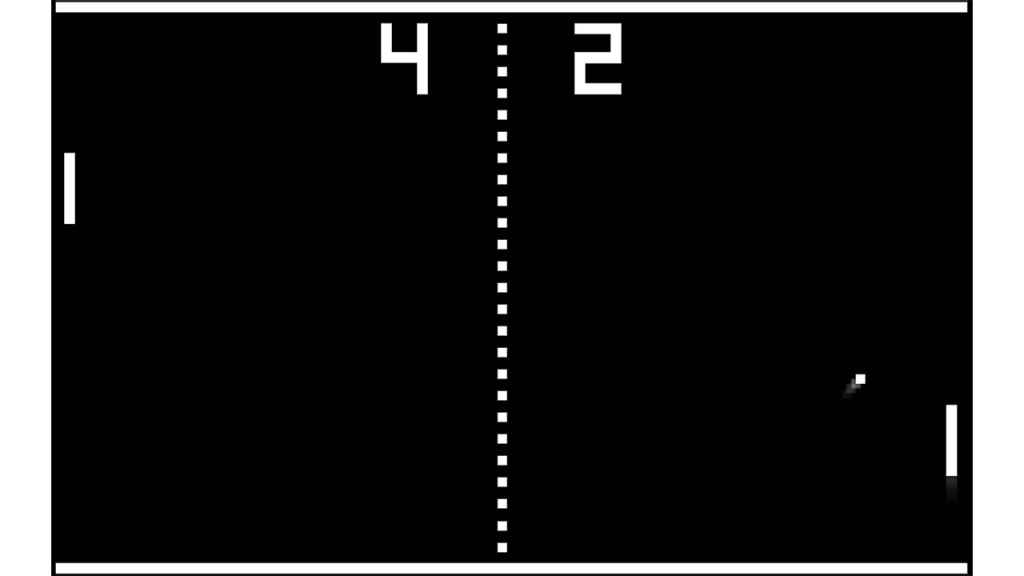

In 1972, Atari’s Pong arrived in arcades. It’s often used as shorthand for “the beginning of the arcade era”, and for good reason: it was simple, instantly understandable, and commercially successful. Wikipedia’s summary is blunt about what it was: a 1972 sports video game developed and published by Atari for arcades.

What did it look like? A black screen, two paddles, a square ball, and a score. That’s it.

So why is this a “graphics leap” at all?

Because it proved that a dedicated machine could draw moving graphics reliably on a raster display (a CRT screen drawing the image line by line), take money, and survive being played repeatedly in public. That reliability created the market conditions for visual progress. Once arcade operators could trust that a game would run all day, manufacturers could justify investing in better boards, better displays, and more ambitious visuals. In a way, this first leap was more about certainty rather than realism. It’s what made certain that arcade games were a viable business.

There had been games before Pong, in fact ‘Tennis for Two’ was built by William Higginbotham in 1958 and even before that there were gamified tutorials to help folks learn how to use the first computers ever built. We’re looking at things where the gaming aspect is the core and not just an accompaniment to a larger feature set.

With Pong, the “technology” here is not a feature like shadows or textures. It’s the package: purpose-built arcade boards tied to displays people already understood. It meant games were no longer one-off experiments. They were products that could be manufactured, shipped, repaired, and iterated on. That industrialisation is the first true leap, because without it, nothing else scales.

How did others respond? They copied the business model immediately. In Japan, Pong inspired clones and competing releases, and the wider arcade market quickly moved towards more varied games. The competitive pressure was obvious even then: if one cabinet is drawing a crowd, you need a cabinet that draws a bigger crowd, and visuals are an easy way to signal “new”. This signalled an ecosystem shift and from this point on, graphics became part of every new arcade machine’s sales pitch.

The 2D sprite and scrolling era

After the first arcade wave, the next leap was about expression. Games needed to communicate quickly to players who might only give them a few seconds before walking away. This is where sprites made all the difference.

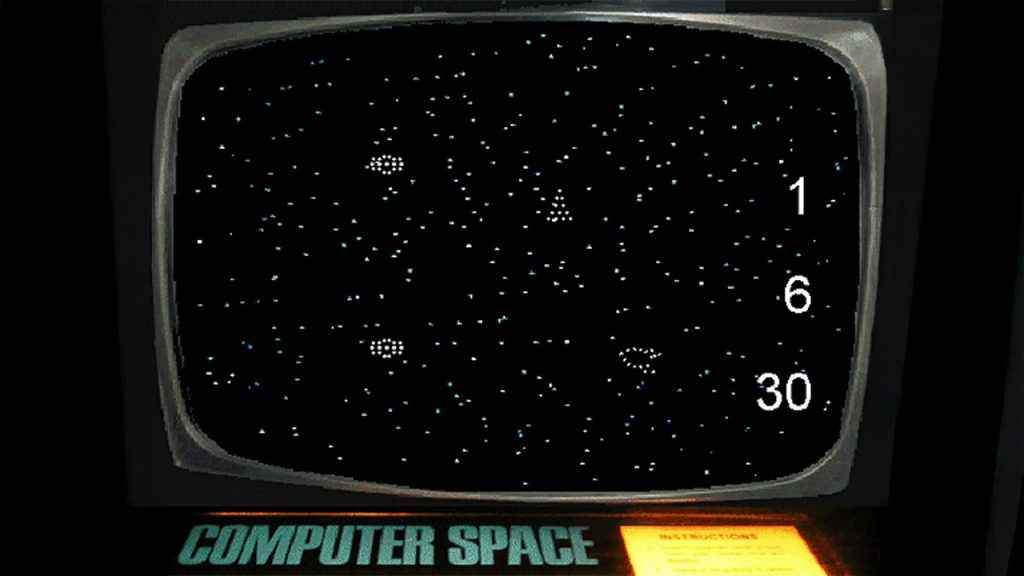

A sprite, in everyday terms, is a small picture that the hardware can move around the screen efficiently. Instead of redrawing the entire scene from scratch every frame, the system can keep a background and move characters on top. That lets games show recognisable characters, animate them, and keep the action clear. The term is believed to have been used in this context by David Ackley at Texas Instruments and is very much based on the fact that a sprite was a supernatural ethereal entity that could float about. The word is derived from the Latin spiritus which means spirit. However, it was Nolan Bushnell, the founder of Atari that came up with the concept in video games when he designed Computer Space.

The reason sprites were transformative is that they turned games into a visual language. Characters got silhouettes. Enemies got distinct shapes. Animations became part of personality. The screen stopped being an abstract playfield and started being a stage. This is also where scrolling becomes a big deal. A scrolling background makes a world feel larger than one screen. It creates the illusion of travelling through space, which becomes foundational for platformers, shooters, racing games, and RPGs.

The big arcade players, including Namco, Taito, and Nintendo, built iconic sprite-based experiences that taught the industry. The important part is not any one company claiming a patent on “sprites”. It’s that the entire arcade ecosystem converged on the idea that character art and readable motion were central to a game’s appeal. Competitors adopted the grammar fast because it solved a practical problem. Sprites and tiles were efficient. They allowed more detail within tight memory limits. They also made games easier to market. A recognisable character on a cabinet marquee is a much stronger hook than abstract shapes.

Why was the impact so big? Because it wasn’t just a visual improvement. It created what you might call the “literacy” of games. The idea that a character can be recognisable at a glance, that movement communicates intent, that backgrounds can guide you, that a world can be traversed, these are still central today. Even in modern 3D games, designers talk about silhouette readability, animation clarity, and visual language, and those ideas are direct descendants of the sprite era.

16-bit Pseudo-3D and faking depth

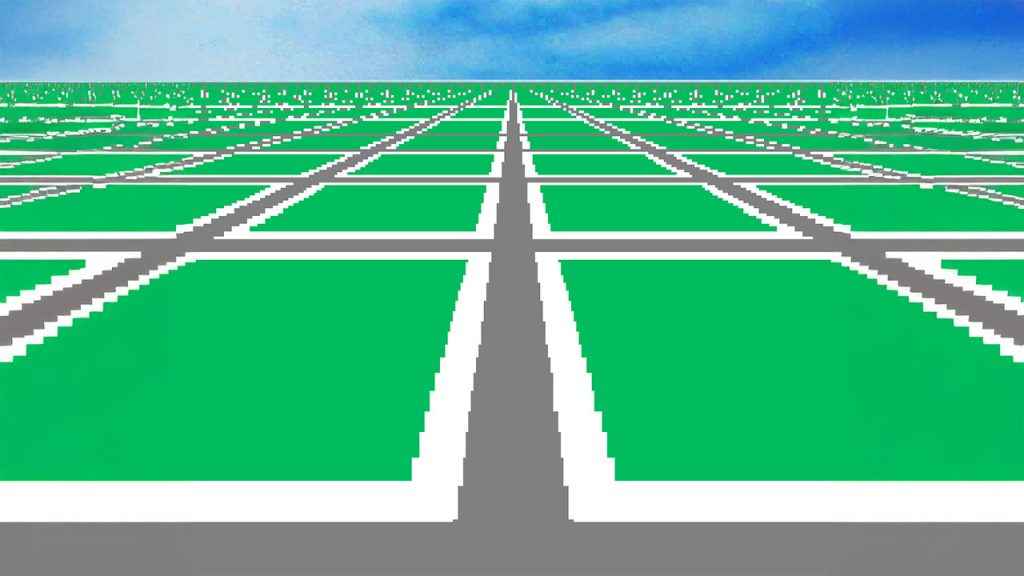

Before true 3D became standard, consoles and arcades spent years learning how to suggest 3D convincingly. The headline example on consoles is Mode 7 on the Super Nintendo. Mode 7 is a graphics mode that lets a background layer be rotated and scaled, which can create depth effects. In plain English, it’s how a flat image can be tilted and stretched so it looks like a floor receding into the distance. So you could perceive depth where there wasn’t any.

This moved the needle ahead because it made certain experiences feel modern even before hardware could do full 3D. Racing games could show a road that curves into the horizon. Flight-style games could show banking turns. The camera could move in ways that felt more “real” than side-scrolling.

This era is sometimes dismissed as a clever trick on the road to real polygons, but it did something deeper: it trained players to expect depth and camera dynamics. It also trained developers to think about perspective, motion cues, and the feeling of speed. Even if the world was still basically 2D under the hood, the presentation began to behave like a camera moving through space.

Sega, meanwhile, had its own identity around speed and spectacle, often using sprite scaling and fast motion cues in arcades. The specifics varied, but the direction was the same: make the player feel like they’re moving through a space, not across a flat plane.

Once these depth illusions became popular, they raised expectations. A game that stayed purely flat could feel old-fashioned, even if it was mechanically strong. That pressure matters, because it creates demand for real 3D hardware. The impact is a kind of cultural preloading. By the time polygonal 3D arrived, players were already primed to accept it. They already wanted the horizon, the camera swing, the sensation of moving through a world.

Early polygonal 3D in arcades

The leap from “fake depth” to “real 3D space” is one of the biggest perceptual shifts games have ever had. And arcades were where that shift became undeniable.

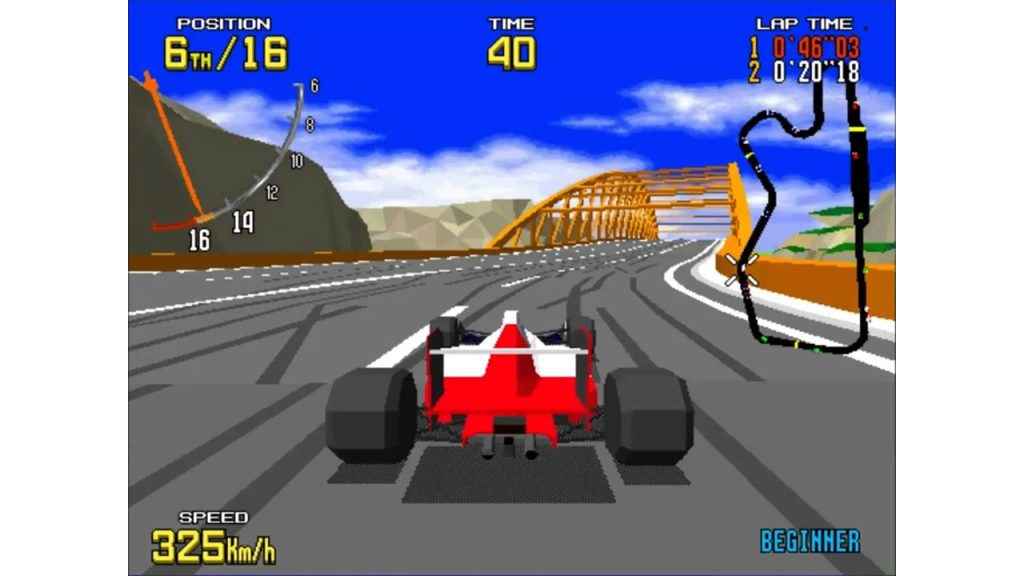

Sega’s Virtua Racing is a key milestone here. It’s a 1992 racing game developed by Sega AM2 for arcades, running on Sega’s Model 1 system. Wikipedia’s page also notes that the game is regarded as influential for laying foundations for later 3D racing games and for popularising polygon graphics among a wider audience.

What did polygon 3D change for an average player? It changed coherence. In sprite-based “3D-ish” games, the world often looks like layers sliding around. It can still be fun, but the space feels like theatre scenery. In polygon 3D, the space becomes unified. The camera can shift and the geometry still makes sense. Turning a corner feels spatial rather than scripted.

Arcades mattered because they were the showroom floor. People could watch a game in motion without owning anything. They could see the camera behaviour and the shape consistency and immediately understand the appeal. Once a major arcade company demonstrates that polygon 3D sells, the rest of the industry starts planning around that future. Other arcade boards pursue 3D capabilities. Console makers start positioning their next hardware as “the one that does real 3D”. From this point on, “3D space” becomes a central expectation for a huge segment of games, especially action, racing, and adventure titles.

Sony PlayStation brings consumer 3D on consoles

Arcades proved polygon 3D could work. The next leap was making it normal in living rooms. Sony’s original PlayStation era is widely associated with 3D becoming the default expectation for home gaming. The key point is not that Sony was the first to ever show 3D at home, but that this generation helped turn 3D into the baseline for mainstream games. In simple terms, it made “3D worlds” feel like what modern games are supposed to be.

A 2D sprite game is about drawing characters and backgrounds and animating them. A 3D game becomes about building assets in a space: modelling characters, rigging skeletons, animating them, building cameras, creating textures to wrap around surfaces, setting up lighting, and defining how the world is assembled.

This shift created entire new pipelines and job roles. It also changed design thinking. Level designers began building spaces that could be navigated in three dimensions. Camera design became a craft. The concept of “where should the player be looking” became far more complex.

Nintendo’s N64 and Sega’s consoles pursued their own 3D identities. The key is not who “won” the generation in sales. The key is that the industry at large accepted the new default: if you were making a big-budget game, you were likely doing it in 3D. This is when “3D” stopped being a novelty or a genre and becomes the standard medium for many types of games. Even when a game stays mechanically simple, it may adopt 3D visuals because tooling, expectations, and marketing all favour it.

Wolfenstein 3D and DOOM

While consoles were making 3D mainstream, the PC was creating a different kind of leap: the feeling of presence through a first-person viewpoint. Wolfenstein 3D and DOOM are classics that form this milestone because it used a 3D perspective while still using sprites for enemies and objects, an approach often described as 2.5D. (The key point is the experience, not the label.) John Carmack’s game engine invented a visual language that is still everywhere.

First-person games need clarity at speed. You’re moving quickly, turning constantly, and making decisions in fractions of a second. The environment needs to be readable. Enemies need to stand out. Lighting needs to guide you without you consciously thinking about it. The viewpoint needs to feel grounded, so your brain accepts the space as navigable.

Even without perfect 3D geometry, this era nailed the feeling of being inside a world. It also created an expectation that the camera can be “your eyes”, not just an external view. And it was also the game that made a lot of gamers come to the brutal realisation that they were prone to experiencing motion sickness.

The FPS template spread rapidly because it was both commercially successful and mechanically compelling. Later engines and later hardware would improve the visuals, but the viewpoint language remained. In other words, this leap shaped how a massive category of games would look and feel. The impact is also cultural. PC gamers began associating “serious graphics” with first-person immersion. That association helped drive demand for better 3D hardware, which feeds directly into the next leap.

Consumer 3D accelerators come out

If there is a single moment when PC graphics became a consumer arms race, it’s the arrival of dedicated 3D accelerator cards or VGA cards or graphics cards. 3dfx’s Voodoo Graphics chip is a central milestone. The Voodoo Graphics chip went to manufacturing on November 6, 1995, and the first graphics card using it, Orchid’s Righteous 3D, was released on October 7, 1996. This was also a slightly awkward era when you look back because the Voodoo Graphics card was a 3D-only add-on, meaning you still needed a separate 2D video card for normal desktop use.

That detail is more important than it sounds. It shows how new the category was. The idea wasn’t “this replaces graphics”, it was “this adds a dedicated 3D engine to your PC”. What did it change on screen? A lot of things that players describe as “it suddenly looked right”.

Texture filtering improved, so surfaces looked less blocky and noisy when viewed at angles. Depth handling improved, so objects overlapped more convincingly. Movement often became smoother because the hardware was built for the workload. Overall, 3D worlds began to feel less like clever software hacks and more like something the machine was naturally meant to do.

There’s also a practical ecosystem shift. 3dfx’s Glide API exists in part because the company believed existing APIs at the time did not fully exploit the chip’s capabilities, with DirectX and OpenGL seen as not ideal for that specific consumer hardware context. That kind of API fragmentation is messy, but it’s also a sign of a young market racing to establish standards.

And competitors had to respond fast. If one company can sell a dramatic visual upgrade as a discrete purchase, everyone else must either match it or risk becoming irrelevant. ATI, S3, Matrox, and NVIDIA all pushed their own 3D acceleration approaches in the same broader period. Some were better than others, but the market direction was set and then came a tremendous amount of fragmentation.

The impact is that the GPU industry, in the modern sense, really begins. Graphics hardware becomes a consumer category you upgrade. Developers begin targeting specific capabilities. Marketing begins leaning heavily on visuals. It’s the beginning of the loop we still live in today.

Microsoft DirectX to the rescue

If a lot of the big graphics leaps are about what you can see on screen, DirectX is one of the rare ones that changed what you don’t see: the plumbing underneath. And that plumbing mattered because, in the 1990s, PC gaming had a very real problem. The hardware ecosystem was messy. Different sound cards, different graphics accelerators, different drivers, and a constant sense that developers were building a game for a moving target.

When Microsoft was about to launch Windows 95, they wanted game developers to build for the new operating system, but game developers were not interested in building for another target in an already fragmented space. So Microsoft introduced DirectX in 1995 as a suite of multimedia APIs for Windows, originally released as the Windows Game SDK. The pitch was straightforward: instead of developers writing bespoke code for every weird combination of PC parts, DirectX would provide a standard way to talk to hardware. That sounds dry, but it was a crucial enabler. Standards are what turn clever tech into an ecosystem, and ecosystems are what turn one great-looking game into an era of great-looking games.

The earliest visible impact was that Windows started to look like a serious gaming platform rather than a productivity OS that happened to run some games. DirectX components like DirectDraw and later Direct3D gave developers a more direct route to performance than the older, more constrained Windows graphics paths. Microsoft even pushed a high-profile proof point by porting DOOM to DirectX as Doom 95 (released in August 1996), and then promoted it aggressively. The specific game matters less than the message: Windows gaming could be made smoother and more consistent if developers built on the new stack.

Where DirectX really becomes a graphics leap, though, is through Direct3D and how it evolved in lockstep with GPU capability. When 3D accelerators took off, APIs had to mature quickly, so developers could use new features without writing hardware-specific code for every vendor. That is why later DirectX generations are often remembered not by the full suite name, but by what Direct3D enabled at the time.

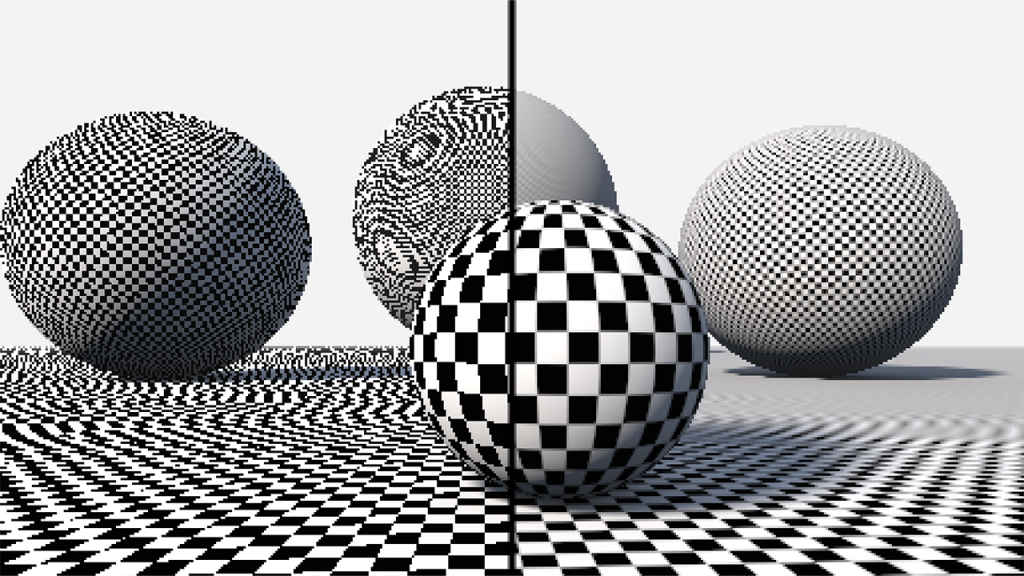

Cleaning up 3D with anti-alising and other filters

If someone says “modern 3D games look better”, a surprising amount of that improvement comes down to one simple problem: jagged edges and shimmering detail. Digital images are made of pixels, and 3D scenes are full of lines and fine patterns that rarely line up neatly with a pixel grid. When they don’t, you get aliasing, which shows up as stair-stepped edges (“jaggies”), crawling shimmer on thin geometry (like fences and wires), and flickering patterns on distant textures (like brick walls and roof tiles).

For years, the industry tried to solve this in a few different ways, each with a different trade-off. It started off with Multisample anti-aliasing (MSAA), the more literal approach. It takes extra samples along geometry edges so lines look smoother, without rendering the entire scene at a higher resolution. It was popular because it made clean edges without massively tanking performance, but it mostly targets geometry edges. As games adopted more complex shading and post-processing, a lot of the visual “crawl” moved beyond simple edges.

Then came post-process methods such as FXAA, which run after the frame is rendered and try to detect and smooth high-contrast edges in the final image. NVIDIA’s FXAA white paper describes it as a screen-space approximation designed for high performance. The advantage is speed and broad compatibility, the downside is that it can soften the image because it’s essentially smoothing what it thinks are edges, without deeply understanding the underlying scene.

That leads neatly to temporal anti-aliasing (TAA), which became the modern “default” in many engines because it tackles the hardest kind of aliasing: subpixel detail that flickers as the camera moves. TAA works by blending information over time, using data from previous frames and motion cues so the game can stabilise thin lines and fine detail instead of letting them shimmer. Unreal Engine 4 leans on it heavily. NVIDIA’s described TAA as a de facto standard.

Alongside anti-aliasing, there’s a second category of “quality leaps” that quietly transformed 3D: texture filtering. A lot of shimmer doesn’t come from edges at all, it comes from textures, especially when you view them at a distance or at a steep angle. Mipmapping is a foundational fix here, it uses precomputed lower-resolution versions of textures, so distant surfaces don’t try to cram high-frequency detail into too few pixels. Once you have mipmaps, filtering methods determine how smoothly the renderer transitions between those levels and how well it samples textures on angled surfaces. That’s where things like trilinear filtering (smoother blending between mip levels) and anisotropic filtering (sharper, more stable textures at glancing angles, like roads stretching into the distance) become big contributors to perceived image quality.

NVIDIA GeForce 256 brings the “GPU” era

As 3D games grew, a new bottleneck became obvious: the CPU was doing too much of the work required to build a 3D scene. It wasn’t just telling the GPU what colour pixels should be. It was often doing heavy geometry maths and lighting calculations. NVIDIA’s GeForce 256 is a famous milestone here. It was announced in 1999, released in October 1999, and that it offloaded host geometry calculations to a hardware transform and lighting engine. And Jensen being the cleaver marketer that he is, GeForce 256 was marketed as “the world’s first GPU” and that integrating transform and lighting hardware distinguished it from older accelerators that relied on the CPU for those calculations.

Let’s translate that. In a 3D game, every object is made of geometry (points and triangles). Those triangles need to be positioned in space, rotated, and projected onto the screen. Lighting calculations decide how bright or coloured a surface should be based on light sources and material properties. If the CPU is doing a lot of that, it becomes a limiter. It can only do so much per frame, and the more geometry you ask for, the more it slows down.

By moving a chunk of that work onto the graphics chip, you change what kinds of scenes are feasible. More objects, more detail, more complex environments, and more dynamic movement become practical. And boy did it catch on. Competitors were racing to match the capability and then surpass it. Once developers can assume that the graphics chip handles more of the heavy lifting, they design their engines around that assumption.

The impact is easy to describe in player terms. Scenes become denser. Games can show more “stuff” without collapsing. The GPU stops being a luxury add-on and becomes the central engine of visual progress.

This leap is also important because it sets up the next one. Once the GPU is doing more of the work, it becomes sensible to make it more flexible. Which leads to the era where developers can write more of the “look” directly.

GeForce 3’s programmable shaders lead the way

“Shaders” is one of those words that can scare off readers because it sounds like an insider term. So here’s a human-friendly way to think about it. A shader is a small program that tells the GPU how to draw something. It might decide how shiny a surface is, how it reacts to light, how it blends with fog, how it glows, or how it blurs. It can also handle screen-wide effects, like colour grading or motion blur.

Before shaders became mainstream, graphics chips had more of a fixed set of behaviours. Developers could pick from the chip’s built-in options, but they couldn’t easily invent new ones. It was like ordering from a menu. With programmable shaders, developers could write their own recipes.

NVIDIA’s GeForce 3 series, which launched in February 2001 was the first graphics card whose architecture supported programmable pixel and vertex shaders. Now games could start doing more expressive lighting, more nuanced surface behaviour, and more cinematic post-processing. Even early on, players saw better water, more convincing metal, richer shading, and more dramatic lighting.

Developers loved it because it changed the pace of visual innovation. If your visuals are defined by programmable behaviour, you can iterate more quickly. You can create a signature look without waiting for hardware makers to add a new fixed feature. You can also scale your visuals more gracefully, because you can write different shader paths for different hardware levels.

Competition responded by building comparable programmability and by pushing shader capability forward rapidly. This is also when graphics APIs and standards become increasingly important because developers want their shader work to be portable across hardware. This step is one of the biggest in the entire history of game visuals: modern rendering is fundamentally a software story running on GPU hardware. The “look” of a game becomes a matter of code and content rather than a matter of hardware presets.

Can it run Crysis?

At some point, certain games become famous not just for being good, but for becoming the visual benchmark everyone uses to judge hardware. No amount of “Can it run Crysis?” memes can bring justice to this era. Crytek became cultural shorthand for extreme PC visuals. The important part here is not the meme value, it’s what those showpieces do to the industry. They reset expectations.

Showpiece games usually do three things. They push world density, meaning how much detail you can see, how far you can see it, and how much of it reacts believably. Then they push lighting and shading complexity so that scenes feel atmospheric rather than flat. And lastly, they push the overall “cohesion” of the image, meaning that assets, lighting, and effects work together rather than looking like separate layers.

Why is this a leap category rather than a single feature? Because it signals a shift in how visual progress is measured. It’s no longer “look, we can do polygons”. It becomes “look, we can do a whole world that looks like this, at this scale, with this kind of lighting”.

The industry responded by treating engines as long-term competitive platforms. Studios invest more in engine technology. Middleware becomes more sophisticated. Graphics settings become more granular. GPU vendors use showpiece titles as marketing anchors. An example would be that the GTA VI trailer showcasing RAGE engine’s prowess came out in December 2023, and we still haven’t got the game. We got GTA VI engine demo before we got GTA VI… I’m not great at doing memes.

The impact is a cultural and economic one. Visual ambition becomes part of platform identity. PC gaming, in particular, becomes tightly tied to the idea of upgrading for better visuals, and engines become the battleground where those visuals are created.

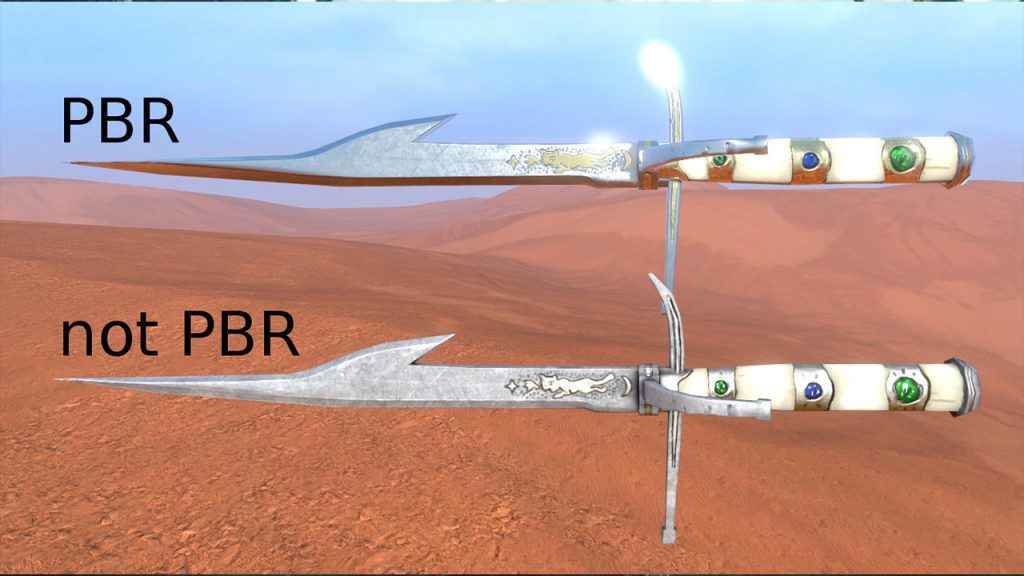

Physically based rendering makes things real(er)

This is one of the most important leaps that many players “feel” without knowing why. In older pipelines, artists often had to cheat materials constantly. A metal surface might look correct under one lighting setup and wrong under another. A rock might look oddly shiny in one level and dull in another. Things could look “gamey” because the rules of light and material response were inconsistent. Physically based rendering, usually shortened to PBR, is a shift in how materials are defined so they behave more like real materials under different lighting conditions.

Game studios love PBR because it makes things more real. Epic’s Unreal documentation frames its physically based materials system as something with guidelines and best practices, signalling that it’s a foundational workflow rather than a single effect. EA’s Frostbite team also documented the move to PBR. The “Moving Frostbite to Physically Based Rendering” course notes describe an overall goal of achieving a “cinematic look” and present moving to PBR as a natural step towards that.

With PBR, if an artist says “this is metal”, it behaves like metal. If they say “this is rough plastic”, it behaves like rough plastic. That behaviour remains more consistent across scenes, whether the lighting is warm, cold, bright, or dim. The result is not just nicer close-ups. It’s a world that holds together. When you walk from a sunny outdoors scene into a dim interior, surfaces still make sense. When you change the time of day, the scene doesn’t suddenly look like different games stitched together. It becomes difficult to justify not using it, because it makes production more predictable and results more coherent.

The impact is enormous for realism, but also for stylised games. Even a cartoonish game benefits from consistent material response because it prevents lighting from becoming chaotic. PBR is one of those leaps that raises the baseline quietly, then years later you realise older games look “off” partly because materials did not behave consistently.

Unreal Engine 4 becomes free, in a way

UE4 deserves its own moment because it did something that’s easy to overlook: it made a modern rendering baseline available to a massive number of developers who were not building their own engines from scratch. This matters because “graphics leaps” are not only about what’s technically possible. They’re also about who can afford to use the technology.

When high-end pipelines become accessible in a widely used engine, the industry shifts. More studios can ship games that look contemporary. More developers learn the same workflows. Tooling improves faster because more people are using it. And importantly, visual standards spread.

This move of releasing a game engine for free with a royalty clause helped the industry tremendously not because UE4 invented every idea inside it, but because it helped turn those ideas into industry defaults. It lowered the cost of entry for modern visuals. We now have a variety of games that suddenly look “AAA-adjacent” even when budgets are not AAA. It also changes competition. Instead of every studio competing on raw engine tech, many studios compete on content quality, art direction, animation, and optimisation. Gamers like this and Unreal makes a lot of money this way. If you want a simple way to see the effect, compare the visual baseline of mid-budget games before widely adopted PBR-heavy engines and after. The floor rises.

NVIDIA RTX ON – Real-time ray tracing hardware

Ray tracing is one of the most famous rendering ideas in computer graphics, largely because it matches how light behaves in the real world. It can produce reflections that show things outside the camera view, shadows that behave more naturally, and lighting that feels physically grounded.

For years, ray tracing belonged mostly to offline rendering, like film and animation, because it was too slow for real-time games. NVIDIA’s GeForce RTX 20 series is widely described as the first consumer product line to implement real-time hardware ray tracing, with the line starting shipping on September 20, 2018.

Here’s the important nuance for everyday readers: games did not suddenly become fully ray-traced movies. They became hybrid. Hybrid rendering means the game still uses traditional methods for most of the image (because they are fast), but it uses ray tracing for specific effects where the payoff is obvious, such as reflections, certain shadows, or some forms of indirect lighting.

This was monumental for a few things. First, it changed what reflections could be. Older reflection tricks often rely on approximations, like showing only what’s already on-screen, or using pre-baked reflection maps. Ray tracing can reflect objects behind the camera, or around corners, or dynamically moving elements more convincingly. Second, it changed the feel of lighting. Even limited ray-traced indirect light can make scenes feel more grounded, especially indoors, where bounced light is a big part of realism.Third, it forced the industry to invest in supporting technologies, especially denoising and temporal stability. Ray tracing can be noisy at practical sample counts, meaning the image can shimmer and sparkle unless you clean it up. Making ray tracing usable in games involves a lot of clever reconstruction.

It wasn’t long before AMD and Intel pursued ray tracing support in their own architectures, and consoles incorporated ray tracing capabilities as part of their broader platform stories. The key is that ray tracing became a checkbox feature in the market. Even if many games use it lightly, the industry now builds around the idea that ray tracing exists and can be used where it matters. Ray tracing raised the ceiling for lighting realism, and it also changed how rendering budgets are allocated. Which brings us to the next leap, because ray tracing created a performance problem that the industry had to solve.

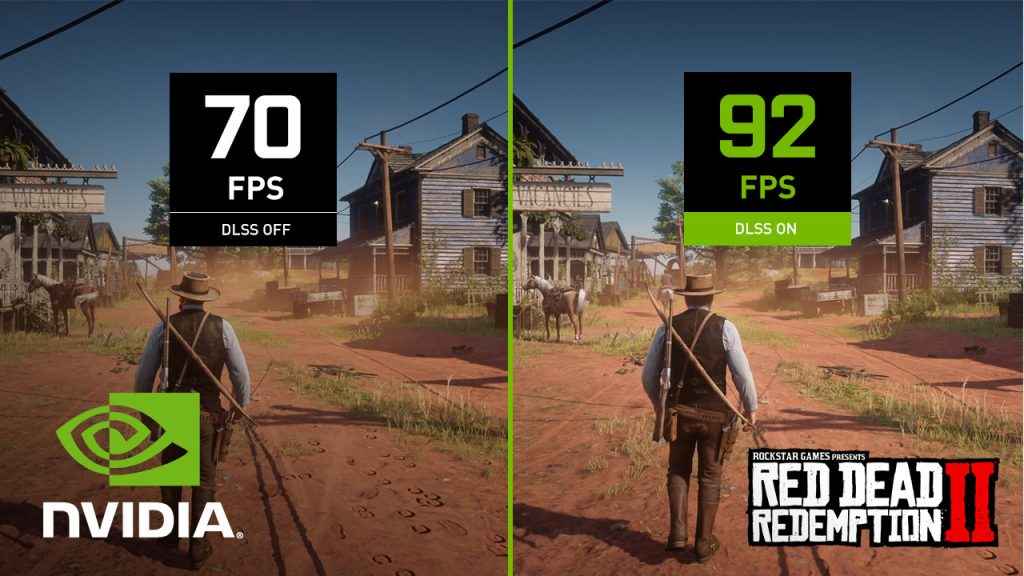

NVIDIA DLSS – AI upscaling and reconstruction

Once you start adding expensive lighting effects, you run into a hard truth: you can’t brute-force everything at full resolution and still hit smooth frame rates. So the industry leaned into a new strategy: don’t render every pixel in the old-fashioned way. Render a smaller internal image, then reconstruct the final picture intelligently. NVIDIA’s DLSS launched alongside their real-time ray-tracing feature in the RTX 20 series. Early implementations were limited because the algorithm had to be trained specifically per game. But with each iteration, they’ve been improving the tech by a significant amount. DLSS 2.0 came out in 2020 with a more general approach. And this is also the time when a lot of “AI” started making its way into the hardware space.

If you’ve been living under a rock, then here’s the quick low-down – your game might internally render at a lower resolution, which means it draws fewer pixels. That saves performance. Then an AI-assisted reconstruction step fills in detail and outputs a higher-resolution image that looks sharper than simple upscaling would. This changes the meaning of resolution. Resolution stops being sacred. It becomes a resource you can spend or save depending on what else you want to do. Want better lighting, more effects, higher frame rate? Reconstruction lets you trade some internal resolution for those benefits without making the final image look like mush.

AMD and Intel were quick to realise that once players get used to “free-ish performance” through reconstruction, it becomes an expectation. AMD’s FSR and Intel’s XeSS exist in this space for exactly that reason. Arguable, AMD’s approach to FSR started off in a more consumer-friendly manner as they didn’t lock the feature to their latest GPUs. While implementations differ between the big three, the market direction is now set: smart reconstruction is part of modern rendering.

Developers couldn’t be happier, games can target more ambitious visuals without requiring absurd brute-force hardware. In a weird way, reconstruction is what helped ray tracing become more usable, because it creates the performance headroom to pay for those expensive lighting effects.

Unreal Engine 5’s Nanite and Lumen make “baking” optional

Unreal Engine 5 introduced two headline technologies that are best understood as productivity shifts disguised as visual features – Nanite and Lumen.

Nanite is about geometry, the detailed shapes that make up the world. Nanite for static meshes uses no traditional LODs (levels of detail), scaling dynamically the number of polygons based on screen resolution.

Lumen is about lighting, specifically global illumination, meaning bounced light that fills a scene and gives it realism. Epic’s describes Lumen as a fully dynamic global illumination solution that reacts to scene and light changes, with examples like changing the sun angle, turning on a flashlight, or blowing a hole in the ceiling. It reduces the need for baking lightmaps and placing reflection captures.

If that was Latin and Greek, then here are the cliffs notes.

For years, developers have relied on two labour-heavy practices. First is manual LOD creation. When an object is far away, you show a simplified version so the game runs faster. Traditionally, artists may need to create several versions of a model, one for close-up, one for medium distance, one for far away. That takes time, and it’s easy to make mistakes that cause “popping” when the camera moves. Second is baked lighting. Many games precompute lighting and store it as “lightmaps”, which look great but make changes slow. If you change the geometry of a room, you may need to rebake lighting, which can be time-consuming and can create iteration friction for design teams.

Nanite and Lumen aim to reduce those burdens. Nanite tries to make geometric detail easier to use without the same manual LOD micromanagement, at least for the kinds of assets it supports. Lumen tries to make lighting respond dynamically, reducing reliance on baking. These are tremendous for saving developer time. Developers can spend less time manufacturing workarounds, more time iterating on the world itself. And iteration speed matters. Many of the best-looking games are not the ones with the most impressive single feature, they are the ones where teams could keep polishing because the pipeline didn’t punish change too harshly.

Other engines and in-house tech are exploring similar directions because the productivity upside is enormous. Even if competitors don’t copy Nanite and Lumen exactly, the trend is clear: virtualised geometry, more dynamic lighting, and reduced baking and LOD labour are becoming priorities.

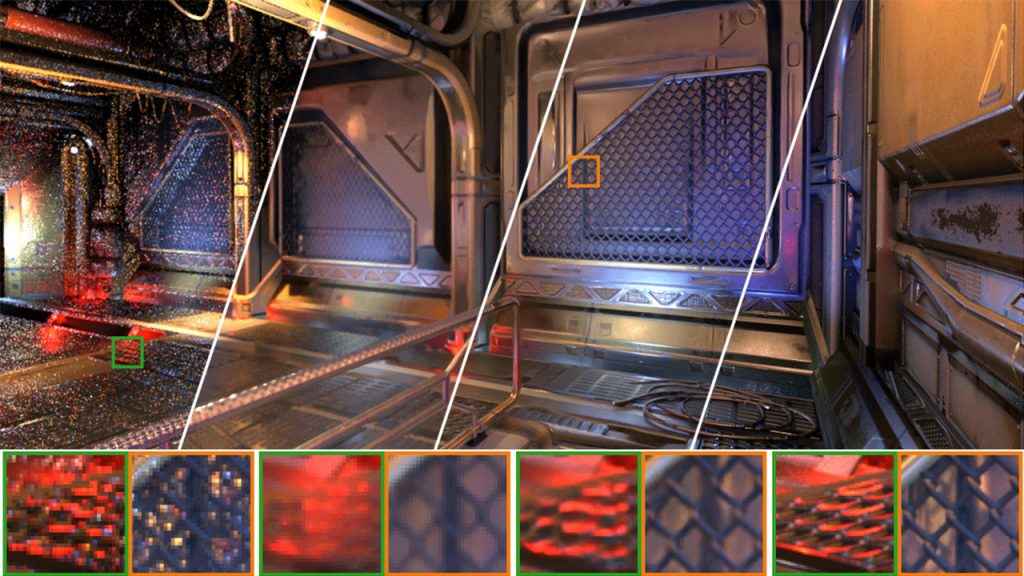

Present time – Neural denoising and neural rendering

If ray tracing and upscaling are the loudest modern leaps, neural denoising and neural rendering are the quieter ones that make the loud leaps usable. Ray tracing tends to produce noise if you don’t take enough samples. Noise looks like shimmering grain, especially in reflections or indirect light. Taking more samples cleans it up, but costs a lot of performance. Denoising is the process of cleaning that noise while preserving detail.

Modern denoisers increasingly use AI or AI-inspired approaches because they can recognise patterns and reconstruct stable results from limited data. The end goal is not just a clean screenshot, it’s a stable moving image that doesn’t sparkle and crawl as you turn the camera.

NVIDIA unveiled their neural add-ons to DLSS at CES 2025. They described DLSS as a “suite of neural rendering technologies” and that captures the broad direction: AI is more than just a bolt-on feature, it is increasingly part of how the final image is produced.

Many modern visuals, especially heavy ray-traced lighting, would be too unstable or too expensive without denoising and reconstruction. Neural techniques help close that gap. They make advanced effects playable rather than merely impressive. Here’s a look at how AMD uses neural filters in their latest version of FSR Redstone.

The “missing but important” leaps

Charting a chronological story like this forces one to pick their battles. That said, a few major ideas deserve acknowledgement because they shaped how games look today, even if they’re harder to tie to one single “pioneer moment” than something like Voodoo or RTX.

One is texture mapping becoming standard, the idea that you wrap an image around a 3D model to give it detail without modelling every brick and scratch. It feels obvious now, but it’s foundational to making 3D worlds look rich.

Another is normal mapping and bump mapping, techniques that fake surface detail by changing how light reacts to a surface rather than adding geometric complexity. It’s a huge part of why surfaces in modern games look textured and tactile.

Then there is HDR and better tone mapping, meaning the game can show a wider range between bright and dark and then compress it in a way that feels natural on a display. This contributes massively to “cinematic” presentation.

Let’s not forget deferred rendering, a method that made lots of dynamic lights more practical in many scenarios and helped shape the look of games in the late 2000s and 2010s.

What’s next for computer graphics?

The through-line across every graphics leap is that realism has never been the only goal, believability and stability matter just as much. Raster arcades made games commercially viable, sprites made them legible, polygons made space coherent, GPUs made complexity practical, and modern techniques like PBR, ray tracing, temporal anti-aliasing, and AI reconstruction are increasingly about making the picture behave consistently in motion, not just in a paused screenshot.

Where this leads feels fairly clear: the “final image” will be less about brute-force rendering every pixel and more about smart synthesis, with engines leaning harder on temporal data, learned reconstruction, and neural denoising to make expensive lighting and geometry look stable at playable frame rates. At the same time, production will keep shifting towards systems that reduce manual labour, meaning more virtualised geometry, more dynamic lighting, and workflows that let teams iterate without re-baking half the game whenever a wall moves.

The endgame probably isn’t perfect photorealism for every title, it’s a world where the hardware and engines are good enough at turning intent into a clean, coherent image that art direction becomes the main differentiator, and the loudest “next gen” moments will come from games that use these tools to build worlds that feel alive rather than merely detailed.

Mithun Mohandas

Mithun Mohandas is an Indian technology journalist with 14 years of experience covering consumer technology. He is currently employed at Digit in the capacity of a Managing Editor. Mithun has a background in Computer Engineering and was an active member of the IEEE during his college days. He has a penchant for digging deep into unravelling what makes a device tick. If there's a transistor in it, Mithun's probably going to rip it apart till he finds it. At Digit, he covers processors, graphics cards, storage media, displays and networking devices aside from anything developer related. As an avid PC gamer, he prefers RTS and FPS titles, and can be quite competitive in a race to the finish line. He only gets consoles for the exclusives. He can be seen playing Valorant, World of Tanks, HITMAN and the occasional Age of Empires or being the voice behind hundreds of Digit videos. View Full Profile