Who will win the next space race

The idea of deploying satellite clusters into space to bring highspeed internet to virtually anywhere on earth is fine enough. But the challenges seem to be many.

While space has been something that has fascinated humans since time immemorial, advances in space science has been a relatively recent development in the human history. It was only in the previous century that man managed to break through to space physically and the farther reaches of the heavens still seems to be a long way off.

Survey

SurveyBut that’s not to say that human endeavour related to outer space is not progressing. In fact, even at this very moment, a new space race is on, and unlike the race for the conquest of space in our past, this time around it’s not nations that are the key competitors but business entities. Also, it’s not for exploring outer space that the new race is underway but to make something happen down here on Earth. And what they aim to do is certainly something that’ll benefit earth’s population: to provide access to broadband internet for the billions who currently do not have the access which many of us take for granted.

Ways to make things out yonder work for the earthlings

The idea is as simple as its execution is complex: to launch mega satellite clusters into outer space that will provide superfast internet almost anywhere on our planet. One of the main terms related to this method is backhaul. Backhaul means the links that have to be established between the satellites and also between the satellites and the internet so that customers can access the internet. This could be made possible using microwave beams or laser beams that function at millimeter wavelengths. This will also require self-aligning systems that can locate other satellites and maintain links even in the case of changes in their relative positions. Another way in which backhaul can be formed for the satellites is by connecting them to ground stations that are connected to major internet gateways.

Bezo’s Blue Origin-World’s first reusable rocket

The key players racing for the pie in the sky

Though multiple companies are involved in this new space race, two of the major firms involved are OneWeb and SpaceX. Though from two different companiesOneWeb is of Great Britain while SpaceX is American, both the companies have the same goal. It’s not just achieving the objective that the firms have to focus on, they’ll also have to contend with regulations regarding gaining of satellite spectrum. And since issues such as assigning satellite spectrum on such massive scales have never been tackled before by anyone on Earth, it’s without the benefit of hindsight that authorities will have to make the necessary decisions.

All this makes it extremely interesting to keep a close watch on the way this new space race is unfolding.

And from what we could glean so far, it certainly seems as though Greg Wyler’s OneWeb is on the right track. The company has not only earned the support of satellite makers such as Airbus, but also that of Virgin Galactic (Sir Richard Branson’s blue eyed vision for the future) and also many other leading corporates and telecommunication providers. The fact that OneWeb is a startup makes this even more impressive. The company which is based in the Channel Islands of Britain intends to launch 600 to 700 satellites as soon as 2019.

The rosy picture of OneWeb doesn’t mean Elon Musk’s SpaceX is withdrawing from the race. SpaceX comes with its own expertise – the California-based aerospace company is not just one of the best rocket manufacturers around, but is also the fastest growing launch service provider in the world.

The company aims to launch about 4,000 satellites within the next five years. And with the backing of heavyweights such as Google and Fidelity who have already announced a $1 billion investment for SpaceX, the firm has every reason to be hopeful of winning the latest space race.

OneWeb’s global web

Kuband and the supposed monopoly of OneWeb

One of the most fascinating things about satellite-based internet is that for it to operate, it will rely a lot on the Kuband radio frequency range. OneWeb was the first company to register its plans with the Geneva-based International Telecommunication Union (ITU) – a United Nations agency for the coordination of satellite spectrum frequencies and orbital slots. This is a fact that OneWeb hastily let the world know. Richard Branson even suggested that this gave Oneweb the claim over the entire Kuband frequency. To use his own words, OneWeb “has the rights, and there isn’t space for another network.”

But as maybe you’ve guessed from the fact that it’s not the only active participant of the space race, Branson’s statements are hardly accurate. The truth is that although OneWeb may be the first to register interest, this does not grant it rights to a monopoly. It’s highly unlikely that the United Nations is going to allow a monopoly, and besides, it’s just better from a customer’s standpoint to have competition – not just for prices, but also for quality of service.

When bureaucrats crash the party

As beautiful as the dream of bringing the internet to practically everyone on the planet is (and thereby making the world truly interconnected), the idea of satellite-based internet will have to contend with being handled by the bureaucracy before it can be realised. The ITU is just the beginning of the story. In fact, one needn’t even consider the ITU as part of the bureaucracy per se. Contrary to what you think, the ITU isn’t a patent office for spectrum. Instead, it’s only a facilitator that ensures that the use of spectrum is equitable and faithful. The consensus which the companies involved in the space race must come to is that they will have to draw from a reserve that none of them may own.

The actual bureaucratic hurdle comes with the fact that just like a country has its sovereign airspace, it also has spectrum control in its territory. This brings national-level bureaucracy into play, making it necessary for companies such as SpaceX to gain the approval of distinct countries for the use of spectrum. Given the history of how even the most progressive of governments have elements in them that are corrupt, this could mean a major challenge for companies in the space race in the first half of the 21st century.

Technically speaking though, there are some technical challenges

Skeptics who view the satellite internet as a pipe dream of billionaires cite some technical problems (which are in turn linked to finance) as the reasons for their skepticism. And one of the main technical hassles they point out is called extreme latency. It’s nothing but the difference in time between a satellite receiving a request and responding to it. This lag would obviously make such things as teleconferencing and online games impractical. Musk and Wyler are both trying to get around this by deploying their satellites in what’s termed as low Earth orbit – some 100 to 1,250 miles above Earth. By placing their satellites closer to home, both SpaceX and OneWeb could bring down latency from 500 milliseconds to 20 milliseconds – roughly the time equivalent for a home internet connection that works with fiber optic in the US.

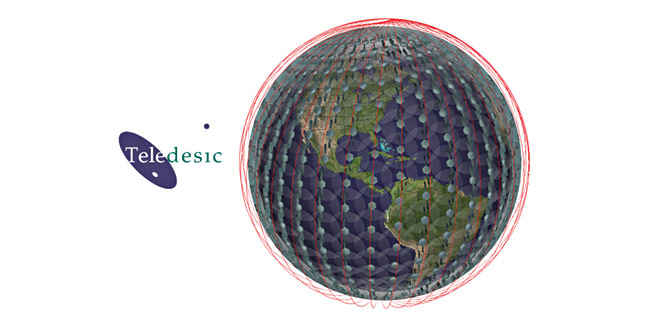

But before you think that this is the solution that puts satellite internet back in business, there’s something else you ought to know: the signal from a satellite in low Earth orbit won’t cover as much surface area of the Earth as a satellite in geosynchronous orbit (about 22,000 miles above Earth). This means more satellites need to be deployed. Even though the price of satellites have come down in the last two decades, it still may not be cheap enough to allow for a significantly larger number of satellites being deployed in such a short timeframe. Augmenting the skeptic’s view is also the matter of failed attempts in the past. For this isn’t the first time that the attempt to bring high speed internet with the aid of satellites is being made. Multiple companies tried to deploy satellites into low Earth orbit with the same intention in the 1990s. One of these companies was Teledesic which was funded by Bill Gates among others. The company planned the launch of 840 satellites but faced setbacks only to cancel its operations in 2002 followed by relinquishing their wireless spectrum rights to Federal Communications Commission (FCC) the very next year.

The failed plan of Teledesic

And then we come to the money part

As mentioned before, there’s the cost incurred with so many satellites (fittingly enough, the figure will be astronomical) that’s a cause for worry for the companies involved. Yet another problem area that the firms will face is with controlling the costs of the internet which they’re going to provide for the billions who don’t have internet access at the moment. And these billions are the poor in developing countries for whom subscription, satellite dishes etc. must come at an affordable price. Also, fiber optic internet connections and wireless mobile data connections are gaining traction throughout the world. This points to the possibility that these modes of connecting the world would prove to be cheaper than serving them using satellites.

The shape of things to come

By this time, it has become rather evident that the space race to bring internet to a larger population is rife with challenges. But the fascinating thing is that companies are still not backing down from the endeavour. Many believe that they will only realise that the costs involved are too high when it’s already too late. They aren’t even backing down after knowing the technical hurdles that are involved, which makes us woinder what it is that they know that we don’t. Hopeful as the fruition of the process seems to be, one aspect that should be taken particular note of is that in this version of the space race – unlike the one between America and Russia that took place during the 1950s – it’s billion dollar companies that are the key players. Governments have been reduced to being mere facilitators. It’s rather obvious to most that the future of the world will be determined by how much we explore (or exploit) resources that are outside our planet. The companies that get a first-mover advantage in the space realm will have a huge impact in shaping the world to come. Should the governments sit back and not have a stake in this?

It’s not just in terms of satellite internet that private firms have become the main players. Even the arena of rockets, which have traditionally been the domain of nation-states, is experiencing this paradigm shift. Recently, Blue Origin a firm established by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos was able to successfully launch a rocket to suborbital space and brought it back down again for a soft landing – making it the world’s first reusable rocket. This is something that could make space exploration much more economically feasible. This is the kind of technology one would expect a government agency such as NASA to come up with, rather than a private firm – especially since the government agencies have been working in the field for a much longer time, and also because they have been complaining about their budgets being cut by governments for the longest time.

SpaceX-charting the heavens

Whatever the case, a clear picture emerges that paints mankind’s future in space as being directed by firms driven by the eventual goal of making a profit. This raises some interesting social questions, such as, is it wise to let the interests of corporations dictate the space race, or should we focus more on the needs of the common people? It is, afterall, the mistakes made by governments and the greed of corporations and individuals that’s caused all of the inequality and suffering of the poor. Is it really wise to expect a solution to emerge by using the same methods that caused the problem in the first place? Only time will tell…

This article was first published in the March 2016 issue of Digit magazine. To read Digit's articles first, subscribe here or download the Digit e-magazine app.