Humanoid robots still can’t match human hand’s dexterity, which is a big problem

Robotic hands remain the biggest challenge in humanoid evolution

Engineers struggle to recreate human touch and dexterity in machines

Without better hands, humanoid robots can’t achieve real-world usefulness

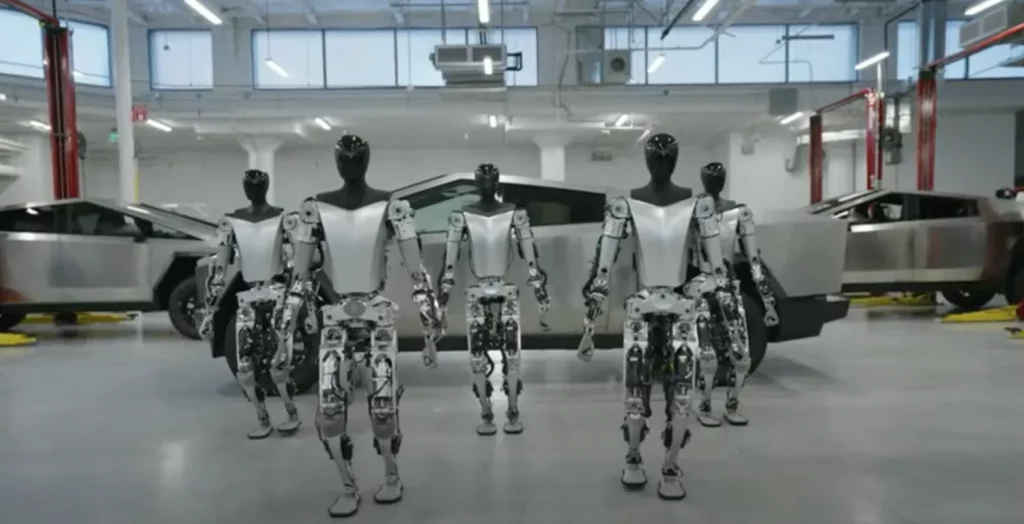

The promise of the humanoid revolution is tantalizing: tireless mechanical workers marching into factories, warehouses, and even homes, ready to fill labor gaps and drive a new era of automation. Companies like Tesla and Figure are racing to make this a reality, yet standing between the two-legged bot and the five-trillion-dollar market it promises is a surprisingly small, but infinitely complex, obstacle: the human hand.

Survey

SurveyHumanoid robots can walk, maintain balance, and even jump with impressive grace, but ask one to pick up a dropped key, thread a needle, or even competently turn a complicated wrench, and the whole system stalls. This challenge, known among engineers as the “hands problem,” is the single greatest bottleneck holding back the widespread deployment of general-purpose robots.

Also read: Are AI chatbots making us worse? New research suggests they might be

The hand problem

In the glossy promo reels of humanoid robots, it all looks effortless. Yet, as recent industry setbacks show, robotics hype inevitably hits reality when it comes to manipulation.

Taking insights from Rupert Breheny’s LinkedIn post on this issue, the temporary halt in Tesla’s mass production of its Optimus humanoid wasn’t due to simple software glitches, but due to “persistent, predictable engineering challenges” in the most complex hardware: the hands and forearms.

Breheny’s analysis pointed to the consequences of prematurely scaling complex, human-like hands, including:

- Motors overheating

- Weak grip strength

- Joint failures

He noted that the systems that make real-world dexterity possible are “high-precision, thermally constrained, and brutally unforgiving at scale.” For a complex humanoid like Optimus, these hands reportedly represent 25% of the total robot cost and a staggering 50% of the engineering challenge, a costly trade-off that led to a reset rather than a minor delay.

Anatomy of the problem

The difficulty lies in replicating the mechanical miracle we take for granted. The human hand is not just a collection of fingers; it’s an intricate, adaptable machine that seamlessly blends mechanics, sensation, and intelligence.

1. The Kinematic Nightmare

A human hand boasts 27 bones and around 20 functional joints, giving it a high number of degrees of freedom (DoF). This allows for the crushing strength of a power grip and the fine motor control for in-hand manipulation—the subtle act of adjusting an object within the palm.

Robotic hands must pack powerful actuators into a small volume, forcing engineers into design trade-offs: greater dexterity means higher fragility, while stronger grips reduce agility.

Also read: EA partners with Stability AI: How GenAI will impact AAA gaming pipeline

2. Touch and Intuition

Dexterity relies heavily on sensory feedback. The human hand has thousands of receptors for texture, pressure, and temperature. Current robotic sensors are still rudimentary by comparison, lacking the seamless integration to guide the robot’s micro-adjustments when facing an unfamiliar object or a slippery surface.

Roboticists have largely solved locomotion (walking) and vision (AI perception). But the final frontier remains dexterous, reliable manipulation (the hands). They are the primary interface between robots and the infinite variability of the human world.

The trade-offs

Faced with this massive complexity, robot makers have chosen different philosophical paths:

| Company/Strategy | Hand Design | The Trade-Off |

| Tesla (Optimus) | Aiming for five anatomically accurate fingers. | High complexity; requires massive AI training and is currently the biggest hurdle for deployment due to reliability issues. |

| Boston Dynamics (Atlas) | Three-fingered ‘gripper’ or tool-like design. | Simplifies mechanics and is stronger, but significantly limits the robot’s ability to use human tools or perform fine manipulation. |

| Academia / Soft Robotics | Using flexible, compliant materials. | Inherently conforms better to objects, but typically sacrifices the precision and ultimate strength of a rigid hand. |

The consensus is clear: to be a truly “generalized robot” capable of operating in human spaces, it needs a human-level hand. Otherwise, humanoids risk remaining expensive toys, as their utility is defined by their Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) on a factory floor, not by how well they pretend to know Kung Fu.

Solving the hands problem will be the final step in unlocking the trillion-dollar potential of the humanoid revolution. Until machines learn to handle the world as deftly as we do, the dream of a truly human-like, general-purpose robot remains – quite literally – out of reach.

Also read: IIT Madras’ semiconductor chip research gets boost from Applied Materials: What it means

Vyom Ramani

A journalist with a soft spot for tech, games, and things that go beep. While waiting for a delayed metro or rebooting his brain, you’ll find him solving Rubik’s Cubes, bingeing F1, or hunting for the next great snack. View Full Profile