We want to tell India’s epics with the quality they deserve, says The Age of Bhaarat team

‘We don’t want to make another small mobile game; we want to push the envelope. The demand has always been there. What was missing was supply. And that’s what we’re bringing,’ says Amish Tripathi, the bestselling author who brought Indian mythology to modern readers through the Shiva Trilogy and Ram Chandra Series. Now, Tripathi is writing for a video game that could position India as a global gaming powerhouse.

Survey

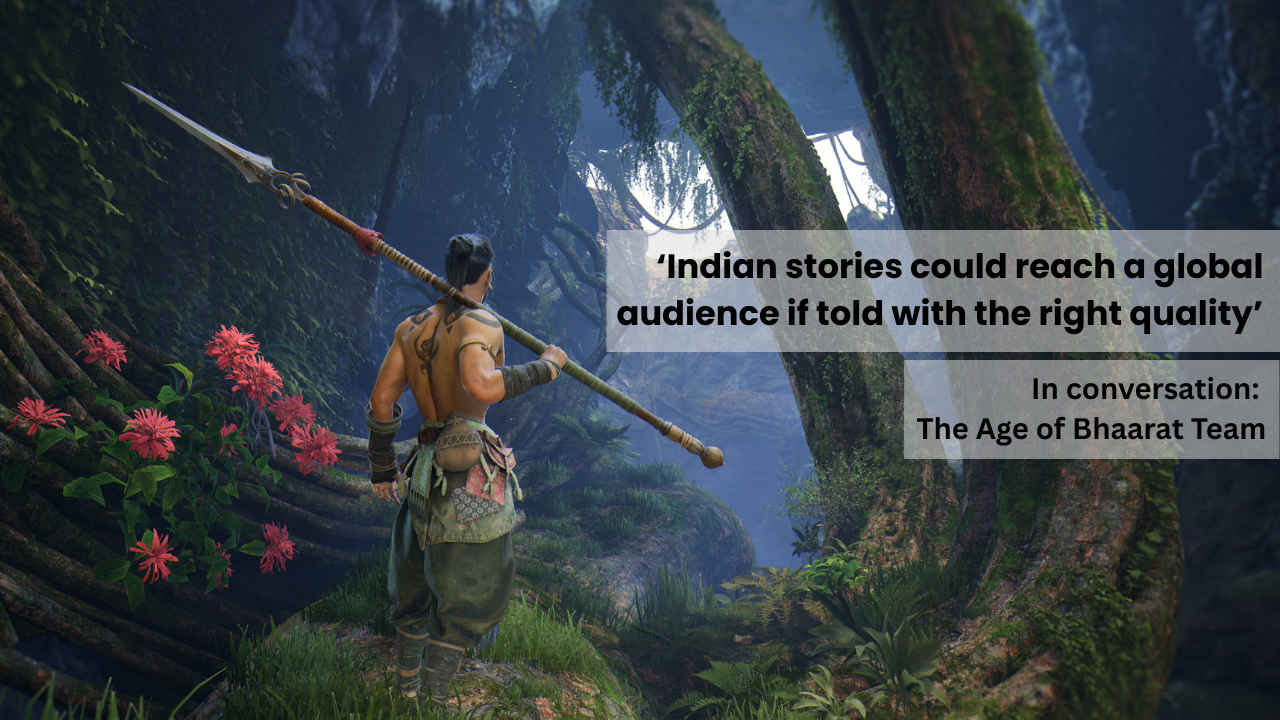

SurveyAcross the world, AAA titles like God of War and Black Myth: Wukong have reimagined mythology and history with breathtaking scale and cinematic storytelling. Yet, despite being home to some of the richest epics ever written, India has never had a true AAA game of its own. The Age of Bhaarat, developed by TARA Gaming, is set to change that.

A collaboration between global producer Nicolas Granatino, AAA veteran Nouredine Abboud, and author Amish Tripathi, the project promises to bring Indian mythology to life with world-class storytelling, cutting-edge visuals, and a global vision. In an exclusive conversation with Digit, the trio opened up about the game, India’s gaming landscape, and what it takes to build a AAA experience from the ground up.

When the three of you first sat down together, what was one shared dream or vision that united you for a game like The Age of Bhaarat?

Nicolas Granatino: What united us was the fact that India is the birthplace of so many incredible epics filled with phenomenal characters and deep philosophy. The Mahabharata and the Ramayana are fantastic, and people around the world know the Gita. The richness of these stories is unmatched.

When we looked at whether they had been treated with the quality they deserve in modern art forms, we realised there was a gap. We saw that Amish had done amazing work through the Ram Chandra Series and Shiva Trilogy, which became bestsellers. That gave us confidence that these stories could reach a global audience if told with the right quality.

Nouredine knew how to build world-class video games, Amish had mastered the art of retelling Indian mythology, and I was deeply interested in what I call ‘heritage cultures’ that have been neglected by Hollywood and gaming studios. For us, three regions stood out: India, Africa with its Yoruba mythology, and the Middle East, which had already been explored through games like Assassin’s Creed and Prince of Persia. Given India’s depth, diaspora, and cultural richness, it felt like the right place to start.

Amish Tripathi: I think Nicolas has given a wonderful global perspective. From an Indian perspective, though, much of our youth today is deeply into gaming. I’m 51, but even I play video games. Many older people still think gaming is a subculture, but the truth is, it’s the main culture now. Globally, it’s bigger than all other creative industries combined.

In India, our stories and cultural nuances are represented in movies and books, but not in video games. That’s something we wanted to change. Most of my readers are young, and many of them tell me they want to see Indian stories in games, not just Western or Chinese ones. Gaming is the perfect medium to introduce our culture to others in a light, immersive way. Players get to experience our stories while enjoying a world-class AAA game.

Where would you say India stands in the global gaming scenario right now?

Nouredine Abboud: I think we need to separate the market’s size from its themes. From a creative standpoint, India is still largely untapped. There haven’t been many games built around Indian mythology or local storytelling. That’s an opportunity. Our goal with The Age of Bhaarat is to open that door, and we believe there are countless stories still waiting to be told.

If you look at it by platform, India today is a massive mobile gaming market. Millions play every day. But in terms of future growth, the blue ocean lies in PC and console. The mobile segment is already mature, not just in India but globally. We saw that during COVID-19, usage spiked, then plateaued once life returned to normal. That’s why our long-term focus is on PC and console, where the potential is yet to be fully realised.

And when it comes to talent, India already has it. For years, global studios have subcontracted parts of their AAA projects to Indian teams. The experience and skill are here. As a new company, we believe the future is bright. Hopefully, our company and our games are here to stay.

You’re positioning The Age of Bhaarat as India’s first true AAA mythological experience, which is a huge promise. How do you plan to meet global expectations and compete with established franchises?

Nouredine Abboud: To compete globally, you have to invest globally. You can’t expect to make a Hollywood-grade production without Hollywood-level investment. We’re not making this game ‘on the cheap’. Our budget and ambition are set to match international standards.

But money alone doesn’t make great games; people do. Our team in Pune is growing fast, already around 50 members strong. We’re hiring experienced AAA talent from across the world while nurturing Indian developers who’ve never had this kind of opportunity before.

I’ve personally worked on large-scale franchises like Ghost Recon, and many of our core team members have shipped world-class games. We’re bringing that expertise here, but we’re also taking our time. AAA games don’t happen in a year. We showed our pre-alpha trailer recently, but there’s still a long road ahead, and that’s how it should be if you want true quality.

Nicolas Granatino: Talent exists everywhere, but when you put that talent in a world-class environment, with funding, mentorship, and global ambition, it thrives. That’s what we’re doing with The Age of Bhaarat.

Look at China’s Black Myth: Wukong. When the team first pitched it, Tencent told them to stick to mobile because that’s where the market was. They didn’t listen. They built a console epic that put China on the global map.

India is at a similar point now: it’s massive, full of consumers, and ready for high-quality original IP. The government understands this too.

Amish Tripathi: As storytellers, we don’t create for where the market is today, we create for where it’s going to be. That’s what visionary creators do. India’s scale gives us a unique advantage. Many smaller countries can’t even build their own defence tech or social media ecosystems; we can.

So yes, The Age of Bhaarat is being built for the future of Indian gaming, not its present. Credit to Nicolas and Nouredine for having that foresight. Sometimes, it takes an outsider’s eye to see what India is truly capable of.

Amitabh Bachchan’s joining Tara Gaming made major headlines. How did that partnership happen, and what made him the perfect fit?

Amish Tripathi: It started when Nicolas and Nouredine told me they wanted a voice that was truly top-tier for the trailer. I said, ‘There’s no one more top-tier than Amitabh ji’. I’ve known him for years. He’s read my books, written about them on his blog, and even mentioned them on Kaun Banega Crorepati.

I messaged him about the project, and being the tech-savvy person he is, he responded almost immediately. He saw the visuals, loved them, and said, ‘Why stop at a voiceover? I want to be involved more deeply.’ That’s how he came on board as a co-founder.

Now, we’re even developing an NPC (non-player character) based on him, which is a key character guiding players in the game. And a fun fact: both Amitabh ji’s son, Abhishek, and my son, Neil, are avid gamers. So, it’s a project that connects generations in a very personal way.

Nicolas Granatino: When we played the trailer for people, everyone instantly recognised his voice. Explaining Amitabh Bachchan’s significance to non-Indians is almost impossible. Imagine Morgan Freeman’s gravitas mixed with Clark Gable’s legacy, and you’re still only halfway there.

His presence also reinforces the universality of the project. This isn’t just about India; it’s about how Indian stories can resonate with the world.

Building any AAA game is hard. But what have been the biggest challenges specific to producing one in India?

Nouredine Abboud: I first worked on high-end games in India back in 2007. Back then, access to talent was a huge challenge. That’s no longer the case.

Our main challenge today is process. When you make a AAA title, you need clear pipelines, coordination, and discipline across teams. Since no one in India has built a full-scale AAA game from the ground up before, we’re establishing that foundation.

The second challenge is perception. There’s still a mild stigma around working in games here. It is not as strong as in 2007, when you had to convince parents that gaming was a real career, but it lingers.

Finally, there’s the technical side. India has more Unity developers because of the mobile market, but we’re using Unreal Engine, the global standard for AAA. So, we’re training and hiring accordingly.

Compared to 2007, the difference is night and day. The infrastructure, internet access, and mindset have all evolved. Now, it’s just about focus, investment, and execution.

What are some structural changes that you believe are most urgently needed here, if there are any?

Nicolas Granatino: I don’t think India needs structural changes so much as it needs execution and capital. Once you have a large-scale project like ours, it naturally trains, mentors, and uplifts the ecosystem.

Look at Montreal, Ubisoft set up there years ago with Assassin’s Creed, and that single project built an entire AAA hub. We’re trying to do something similar here: use Indian talent, Indian mythology, and world-class processes to create something irresistible.

And that’s the magic combination of global quality with local soul. Once people see that it can be done from India, the rest will follow.

Speaking of India’s gaming landscape from a broader point of view, what structural changes do you believe are most urgently needed, if any?

Nicolas Granatino: I don’t think major structural changes are needed. It’s really about putting in the work and the capital. Once you have a project on a huge scale, it naturally becomes a catalyst for growth. You can mentor, train, and hire talent, and introduce them to proper AAA processes. Many Indian subcontractors already work for international studios, so the experience exists. What’s missing is large-scale ownership.

We also have world-class VFX studios here, both from Bollywood and Hollywood, that are eager to learn how to apply their expertise in gaming. So, the foundation is strong, it just needs focused investment and execution.

Another big advantage for India is its engineering and computer science talent. That’s what powered its outsourcing industry, and it will be a huge asset for high-end game development too. Combined with the country’s creative ecosystem and its technical strength, India’s position is much stronger than people realise.

Amish, you’ve reimagined Lord Shiva and Lord Ram for modern readers through your books. How different is it to write for an interactive world compared to a book?

Amish Tripathi: It’s very different. When you’re an author or filmmaker, you control the narrative. You decide the beginning, middle, and end. Readers or viewers can choose to engage or not, but you’re the one in control.

In a video game, that dynamic flips, and the player is in control. As an artist, it’s a complete mindset shift. You’re not crafting a linear narrative; you’re building an entire universe where multiple paths exist, and none of them can contradict each other. It’s more complex, but also far more exciting.

Then there’s the sheer scale. A good AAA game can have 70 to 100 hours of gameplay, which is like making 30 movies. The amount of content you need to create is enormous.

And finally, there’s the cultural context. In books, I’ve always written respectfully about our traditions, and that hasn’t changed here.

What makes The Age of Bhaarat relatable to players who may not know the Mahabharata or Ramayana?

Amish Tripathi: From a narrative standpoint, we genuinely believe our epics are both deeply philosophical and incredibly cool. The stories themselves are universal: full of emotion, power, and meaning.

That said, when you’re making a AAA game meant for global audiences, you need to balance authenticity with accessibility. We’re not going to overload the script with Sanskrit. If there are concepts that Indians instinctively understand but global audiences don’t, we’ll introduce them gently.

Even small things like names matter. Something like Hiranyakashyapu rolls easily off an Indian tongue, but might be intimidating for others. So, we’re simplifying without losing essence: keeping it familiar for Indians but approachable for everyone else.

Nicolas Granatino: When we announced The Age of Bhaarat, we actually did street interviews in India. I was amazed at how passionate young people were. They knew the characters, they understood the stories, and they were excited.

If we tried the same in London or New York with the Bible, I doubt we’d see that level of enthusiasm. The fact that these epics have stayed alive for thousands of years speaks to their modernity and universality. You see it everywhere. Even in Monkey Man, Dev Patel’s film, the mother tells her son stories of Hanuman. Every Indian child grows up hearing those stories. It’s part of daily life.

And as Amish said, Journey to the West, the Chinese epic that inspired Black Myth: Wukong, actually traces its roots to Hanuman and India. Even Tencent acknowledged that Wukong is a descendant of Hanuman. That’s the kind of cross-cultural power Indian mythology has and why India is the perfect place to build something truly global.

For a country that has inspired countless myths, it’s poetic that India’s first true AAA game is finally emerging from its own stories. The Age of Bhaarat seems to be more than a milestone for Indian gaming. The game is the beginning of a new era where local legends meet global ambition.

Also read: BGMI International Cup 2025 kicks off in India: Teams, venue, and all details

Divyanshi Sharma

Divyanshi Sharma is a media and communications professional with over 8 years of experience in the industry. With a strong background in tech journalism, she has covered everything from the latest gadgets to gaming trends and brings a sharp editorial lens to every story. She holds a master’s diploma in mass communication and a bachelor’s degree in English literature. Her love for writing and gaming began early—often skipping classes to try out the latest titles—which naturally evolved into a career at the intersection of technology and storytelling. When she’s not working, you’ll likely find her exploring virtual worlds on her console or PC, or testing out a new laptop she managed to get her hands on. View Full Profile