Guide to the maker scene in India

There's a secret revolution gathering steam in the country. Here's how you can be a part of it.

Before we take on understanding the mammoth maker movement, you should meet Bob. He is a dancing robot that enjoys a considerable amount of air time online. Bob is made up mostly of circuits though his shiny blue suit is a polymer that was 3D printed at a Mumbai-based makerspace called Maker’s Asylum.

One would be mistaken to assume that the maker movement began from makerspaces because like all quiet subcultures, makers too started at home. They slowly grew to find others like them and occupied physical spaces which they began to call by a cool name. Makerspaces can be simply defined as a gym for tools where makers, people like you and me, go to flex their creative muscles and build things.

Survey

SurveyBut back to Bob. This robot stands ata height of 10 inches and can walk, race and dance. It is for these many talents that ‘he’ is treated like a child who is called on to entertain guests. But unlike most children are made to believe, Bob isn’t one of a kind. In fact, the plans to make the humanoid are available in painstaking detail on Instructables for free. This means there have been multiple Bobs before and after this Mumbai version was born. Some of them and their makers even show up in the comments section.

Maker Mela 2015, organised in Mumabi’s Somaiya College of Engineering by their makerspace. Riidl saw a footfall of 50,000 visitors and 100 makers

The maker movement is an umbrella term for tinkerers, inventors, innovators, designers, artistes, DIY enthusiasts and hobbyists who like to work with their hands. The culture is characterised by learning by doing, iterating using digital manufacturing tools and sharing knowledge with a community of peers.

Besides being simply adorable, Bob is oddly representative of the maker movement. Makers who built Bob, the first, decided to document their efforts and share it with the online world. Makers in Mumbai who decided to access these open files and assemble Bob were learning about robotics while they built this humanoid robot. And finally, while Bob may not have impacted social change, he facilitated learning, sharing and building without seeming like work which is important to understand the maker psyche. According to experts like Chris Anderson, former editor-in-chief of Wired magazine, this is the essence of how the maker movement took off. And it was a long-time coming. In his 2012 release Makers: The New Industrial Revolution, he elaborates on the circumstances that led to the movement and the labelling of a community that long preceded its popularity.

We are all born makers, he argues. All of us while aged five and below remember playing with building blocks. So what if you built buildings only to knock them down with your toy car later. The maker movement clings to this very primitive ideology — men like to build, men like to break. If it comes to us naturally, it must be good.

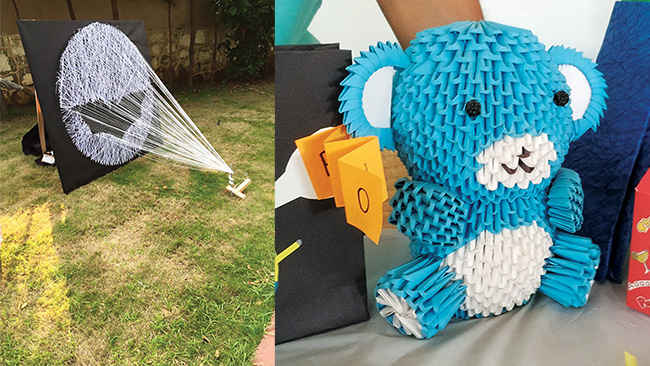

Laser cut toys

But for all those who have recently got on the maker bandwagon, there’s news. The first makers were probably cavemen; they simply didn’t have a fancy term for what they did. Human psychology makes us want to better circumstances and build things that will ease life. So there is really nothing new except the term itself. Commentators have compared the word ‘maker’ to its contentious counterpart — hipster, though only ironically so, of course. Yes, makers like hipsters were always around. They were probably relegated to the corners as hobbyists who enjoyed wood carving or building miniature models of aircraft to scale, men who enjoyed fixing things around the house instead of calling a handyman and craftsmen and women who honed their skills without making too much of a noise about it. Perhaps all it lacked was a formal term, a cool attitude and a rationalisation of how it can impact economies to catapult it to centre stage. It only makes sense that when money is involved, national interests are met, and everything seems a whole lot more important.

Woodworking workshop at Maker’s Asylum, Mumbai

There are a number of reasons that this is the right time to be acknowledging the maker culture. Like all wonderful things, it has much to do with the Internet. Post the industrial revolution in the 1800s which represented the transition to new manufacturing processes that made it possible to mass produce, the age of the Internet followed where the masses were suddenly able to communicate openly, in real-time and across geographical boundaries. We turn to Anderson again who construes, “The real revolution here is not in the creation of the technology, but the democratization of the technology. It’s when you basically give it to a huge expanded group of people who come up with new applications, and you harness the ideas and the creativity and the energy of everybody. That’s what really makes a revolution.”

So now, while production of goods was concentrated in the hands of a few; feedback on usage, quality and features was being communicated back to big brands by the consumers. Out of nowhere, big companies were looking at mammoth amounts of data like they had never seen before. Communicating with users one-on-one was possible and dynamic brands were eager to use this insight to better their offerings. By this time, most companies had embraced the digital revolution, Indian families jumped on board to educate their children to grow up to operate in software-related job profiles for the barrage of work opportunities that it promised and delivered on a decade later. It is fair to note that these well-meaning parents were not wrong; there is still no short supply of job openings for software engineers the world over.

There was also a cultural movement brewing when hackathons took place in European cities; Germany is credited for being the first though adequate documentation isn’t available. Here, groups of young programmers were developing a sense of community and gathering to combine their prowess with technology for a common cause. They didn’t start off saving the world; they started out with the premise of sharing knowledge, making electronic art and other such transient intentions. What they managed however was to create a sense of community, open sharing and goodwill.

But getting back to business and how computer-integrated manufacturing software was also available to those unsatisfied consumers to tweak, bend and create better versions of products they wanted to see in the open market. Then came additive manufacturing which acted as the game changer though, it is imperative to note that none of this would have been possible without the first few players involved. The 3D printer, here, is king. It allowed for computer generated digital files to feed into a machine that used material (plastic, metal, concrete, ceramic) to be layered to create products in a fraction of the time. A volley of product designers could communicate on the cloud, design a toy, tool or prosthetic limbs even and consumers can print it out at home without any additional costs to customs or transportation. Bits could be converted to atoms and there was no looking back. From here, it was a short skip and jump to the consumer becoming the designer.

Origami workshop in progress

For Tanmay Shah, Innovations, Leadership Team of Imaginarium, that entered the rapid manufacturing and prototyping industry a decade before mainstream media fully understood the importance of 3D printing, it was a lesson in restraint. They started out with prototyping for jewellery manufacturers who would otherwise work with a cheaper metal to prototype and then graduate to precious metal. Today, they collaborate with clients across healthcare, automotive, architecture and consumer industries. The Imaginarium Medical Team is working with doctors to create a modern 3D printed hand cast for fractures which is custom fit, custom designed, lightweight and water resistant. Imagine not having to use a pencil to poke inside a bulky Plaster of Paris cast to soothe an itch. Transformative change! In the jewellery industry, when constraints of traditional manufacturing are eliminated, designers can set their imagination free and create shapes and forms that were hitherto impossible, explains Shah.

Their biggest yet most understated venture is realised through Imaginarium’s Metamorphosis Cafe, an informal learning facility of sorts where they hope to empower others with the knowledge of how to maximise the use of 3D printing technology. It will help anyone set up a 3D Printing experience zone or lab in their school, college or workplace, along with planned workshops, activities, materials and support.

Of course, the colossal brands like Intel, Wipro and GE were quick to join in on the 3D printing bandwagon. But the story of the little guy is a lot more fascinating. So now “consumers-turneddesigners” started to create their own products instead of waiting for the big companies to take their inputs into consideration and get it right. An ecosystem of portals and online market places to take care of the menial tasks like selling, sharing and collaborating sprung up.

So what is the difference between innovation labs at multinational corporations and makerspaces?

“The three immediate differences that come to mind are scope, resources and community,” says Shah. While corporates most likely restrict the areas of innovation to their specific domain or industry, a makerspace is a zone of unhindered innovation. “Sometimes, there need not even be a business motive for a makerspace project. Business drives innovation labs at corporates, passion drives projects at a makerspace,” he adds. With regard to resources, corporates, once committed to innovation, are willing to pump in any amount of resources required to realise ideas. On the other hand (and sometimes as a plus point), makerspaces globally thrive on limited resources in terms of tools, technology, space, etc. Does this frugal approach aid innovative thinking? Perhaps, is Shah’s answer.

Makerspaces do bring in more men than women. This Shibori dyeing workshop brought a refreshing change in members.

“The biggest difference, and the decider that turns the needle towards makerspaces is the power of communities that it creates. Having the most creative minds across diverse disciplines willing to contribute and collaborate voluntarily on ideas is an asset that is extremely difficult to create within a corporate organisation. Often, it is only when the motivation to make and build is non-monetary that the best ideas can come alive,” says Shah. For individual makers, the fact that consumers were willing to pay a premium for products that were intelligent and artisanal all at once, helped. Relationships were built on the basis of this; zero to maker, maker to maker and maker to market. Makerspaces functioned like makeshift coworking spaces were the same sense of community prevailed; artistes collaborated with techies who worked with handymen. Fab Labs and for-profit ventures like TechShop that followed a similar working principle also gave makers a physical address. Startups that were driven by hardware or physical goods found an avenue to prototype at a lower cost and churn out a final product that was on par in terms of quality when compared to corporate offerings and at a fraction of the cost. They were also able to tap into their free-loving community of designers, product strategists and marketing professionals that formed the ecosystem.

Emerging platforms like Thingiverse, Instructables and Make-zine made it possible to share knowledge and designs with the niche community, and Autocad and Sketchup provided easy-to-use software for the designer community to work in tandem with innovators while using 3D printers. Cubify, Shapeways and Ponoko set up platforms for designers to share their designs so users could pay to download and print them elsewhere in the world.

Spandan Banerjee makes skateboards under the banner Tattva boards

Makers connected to other makers to develop kits that could cut down the running around and rigmarole of finding and fitting electronic components by selling kits. Ankit Daftery, founder of Daf Labs, provides basic kits to makers, for example, TinyBoard is an Arduino compatible board developed to have micro-controller board with a small footprint and low cost for use in making everyday objects interactive, and finished goods, for example, a breathing mood lamp, to consumers. The TinyBoard was an early experiment, and was received rather well. “Makers were looking for something that could be used as a cheap, lesser-featured Arduino that could be programmed easily and put into small places and objects to make prototypes and installations cheaper but more importantly, to a more realistic scale,” says Daftery.

Ankit Daftery, founder of Daf Labs provides basic kits to makers, for example, TinyBoard is an Arduino compatible board developed to have micro-controller board with a small footprint and low cost for use in making everyday

objects interactive

MakerBot, 3D Systems, ShopBot and Arduino came in for technical assistance. So suddenly, all the mom and pops styled stores were on a level playing field when it came to quality thanks to additive manufacturing that brought democracy to the factory. In fact, they could give users something their giant counterparts couldn’t – customised attention to detail.

All consumers needed to do was head to Adafruit, Kickstarter, Indiegogo, Etsy or even eBay to buy, sometimes even before the production run was planned out. For the $33.7 billion eBay, their decision to stock independent maker’s goods right next to those manufactured by large chains in the cyber bazaar is telling.

It’s always time to take a possible revolution seriously when the money bags start noticing it. In 2013, GE launched FirstBuild, an open platform for designers, artistes, technologists and the next guy to collaborate on ideas to refine existing GE products. Tapping into the maker culture is high on the agenda for corporates who like to throw around the word “disruptive” when referencing the maker movement.

Pavan Kumar from WorkBench

To get back briefly to the guys at hackathons who had built for themselves a physical space to hack called hackerspaces, they experienced the natural progression to require hardware to support the software they used. Here, hackerspaces began to introduce tools such as hand tools, power tools and additive manufacturing tools. The word ‘maker’ was still unheard of.

There is a considerable amount of urban lore about how the term ‘maker movement’ came to be. One such tale starts off with a man named Dale Dougherty, founder of Maker Media that publishes the infamous MAKE magazine which came out with its first edition in 2005 in California. The bi-monthly which aimed to document the work of DIY enthusiasts and hands-on tinkerers of technology was to be called Hack originally. It was Dougherty’s daughter, legend has it, who suggested ‘Make’ since the word hack had been sufficiently used to label software tinkerers. As the premier voice of makers in America where the movement metaphorically caught steam, it gave rise to the empire that is now Maker Media that consequently started Maker Faire, a flagship carnival of and for makers. And so it came to be that the maker movement was born. That, or the story was completely hogwash but in any case, the term seems to be here to stay.

Whether the maker movement is making a dent in the American economy can perhaps be explained through statistics; in 2013, Shapeways set up 13,500 online storefronts, Etsy sold a total merchandise of $1.35 billion from 1 million active shops. The figures are part of the Impact of the maker movement report by Deloitte centre. The most impressive of this litany of numbers however is one titbit that tells us how Facebook acquired Oculus Rift for $2 billion. This isn’t impressive, of course, till you realise that the Oculus Rift took off as a Kickstarter offering where it managed to crowdfund $2.4 million.

Seeja Sudhakaran uses a software called Grasshopper to create architectural designs around set parameters. She then laser cuts her models

But why are makerspaces which function as a hot mess of innovation relevant to established industries? “Those organisations/individuals who fail to embrace the coming waves of open innovation, open source hardware and software and truly cross disciplinary collaboration are going to die out. At the same time, the Maker Movement will live up to its currently hyped expectations only when it finds a sustainable way to convert ideas into refined, ready for market products and services, and in the process create valuable IP.” says Shah.

Closer to home, it is meaningful to know how and why the maker movement is going to make waves. Currently, there are around 20 makerspaces in India, most of whom aren’t more than three years old. Maker’s Asylum is joined by Curiosity Gym and Riidl in Mumbai, Nuts and Boltz in Delhi, Collab House and Potential Labs in Hyderabad, Workbench Projects, The Workshop and Eden in Bangalore, and Maker Loft in Kolkata. Moreover, companies are investing their R&D budgets into internal innovation hubs which function much like makerspaces minus the access to general public. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s big push to Make In India could be seen as a fertile bed for the maker movement. According to a World Economic Forum report, manufacturing currently contributes approximately 14.2% to India’s total GDP, which is lower than other emerging economies recognised for delivering significant competitive advantages for manufacturers, including China (32.4%). In 2011, India announced its National Manufacturing Policy with an objective to increasing manufacturing sector growth to 2-4% more than GDP growth. To do this they planned to increase manufacturing’s share of GDP to 25% by 2025. According to their estimates, it promised to create 100 million new jobs by the same deadline.

Making a mechanical mouse trap out of laser cut parts in Maker’s Asylum, Delhi

For a country that comes with a rich skillset of handicrafts, the maker movement is the new wave cottage industry at play. Modi’s move for India to be seen as a competitive manufacturing and production hub rather than just a service oriented nation with cheap workforce. In the same vein, makerspaces are seen as mini production units, a nursery for consumer goods and a place where more students are trained practically to transform them to a skilled workforce. Heavyweights like Maker Media seem to be behind the proliferation of the maker culture in India. This is evident from their backing festivals like Maker Fest which will celebrate their second edition later this month in Ahmedabad; 30,000 spectators have already signed up, and the first edition of Mini Maker Faire was held in Bangalore last year.

It may seem like a loaded movement to be a part of but visit a makerspace and you are more likely to find yourself in a playground for grownups. Makers aren’t nearly as menacing when you see them racing RC cars, whizzing drones, manoeuvring hovercrafts, 3D printing minions, etc. And of course, there’s Bob — the robot that likes to dance.

Yolande Dmello

Yolande is a journalist by profession and a dreamer by choice. She’s worked with dailes such as Times of India, Mumbai Mirror, DNA and MiD DAY during a 5-year stint. In her free time, she likes to rhyme about killer robots and dance with her eyes closed. View Full Profile