How to make the best use of maker spaces in India

Makerspaces that promise easy, affordable access to hobbyists and aspiring hardware entrepreneurs are springing up around the country. Is India ready for the anti-school?

In May, Sanjiv Valsan, Vishwaraj Doshi and Rujai Mehta — third year engineering students from DJ Sanghvi College of Engineering, Mumbai decided to build a formula style racing car. The dream was big and the team sizeable — 30 students across eight departments signed up to help. The car that was to be designed, built and tested, and would go on to compete in an international design competition to be held in Hockenheim, Germany. Valsan and team had a winning idea. They decided to use a motorcycle engine in the car. This meant all corresponding parts needed to be built from scratch since they could not be sourced from existing cars. When it came to manufacturing the parts however, there was just one problem — they didn’t know where to start. That’s when he decided to approach Maker’s Asylum, a makerspace in Mumbai, for help. Here, they were able to access 3D printers to print plastic moulds of any and all parts they may have needed for the car. Countless iterations could be made and then the final piece outsourced to be manufactured.

Survey

SurveyThe 2,000 sq ft makerspace doubled up as their garage where hand tools and power tools were handy. The car remained parked for over two months at the space and those who dropped by the makerspace often offered tips on cooling, transmission, suspension and steering techniques. “There is a wide variety in the kind of people that you get exposed to at a makerspace. You can have an aeronautical engineer, an origami artiste and a school kid walk in on the same day. We got some interesting input, but most were simply curious,” explains Valsan.

For participants of the car-build who had also competed the previous year, it was a refreshing break from having to rent out garage space, borrow tools from friends’ dads and call up professors when stuck with a glitch.

So, what is this magical makerspace? Think of it as a library for tools, explains Vaibhav Chhabra, founder of Maker’s Asylum. “Instead of books, we offer access to tools,” he says. It’s a community space which means open access to public that is democratic and not restricted to what you studied in college. In fact, the rules don’t change even if you didn’t go to college at all.

At Maker’s Asylum, Mumbai, carpentry is a hot selling workshop with maximum female participants

In addition, costs of tools are split by many. Hence, a 3D printer which costs upwards of Rs 1 lakh and laser cutters which will set you back by Rs 3 lakh each are accessible for a nominal usage fee. Moreover, if you are curious to learn something like carpentry but don’t trust yourself to keep at it for too long, investing in tools and materials may not be a wise decision. Think of how you paid for that gym subscription for the whole year only to cool your muscles for the better half of the calendar.

There are more than 20 makerspaces in the country, most of which have been established less than three years ago. Curiosity Gym and Riidl in Mumbai, Nuts and Boltz in Delhi, Collab House and Potential Labs in Hyderabad, Workbench Projects, The Workshop and Eden in Bangalore, and Maker Loft in Kolkataare some of the popular ones.

Utkarsh Kumar Gupta builds an miniature Eiffel tower using laser cut cardboard pieces at Maker’s Asylum, Delhi

Here, you can walk into a makerspace and try your hand at it before you commit and put money down on sanders, lathes and rotary tools. If carpentry isn’t worth wasting your wood, there’s metal work, taking apart bikes, racing RC cars, building drones, and introduction to electronics through breadboards, Arduino, Raspberry Pi, etc. Oh yes, they also like breaking things. But not for nothing, education is a major role of the makerspace. But learning isn’t put forth as a formal curriculum. Instead, it comes to you as a byproduct of building. There may be short courses and workshops led by community mentors who have earned their title by giving back to the space or because they are domain experts. These mentors will guide members through difficulties but for the most part, you are on your own. And for this reason, the maker movement is sometimes also called and confused for the DIY movement. It isn’t wrong to call DIY enthusiast makers but it’s more of a subset than an interchangeable term.

On a typical day at a makerspace, in addition to students trying to test theories they have learned in class practically, you will find hardware entrepreneurs trying to prototype their next product, dads teaching their sons to build a table from planks of wood, artistes trying to create art that responds to audiences and designers upcycling junk to kitschy furniture. It’s too early for makerspaces to zero in on the target audience for their offering. In fact, founders Chhabra and Pavan Kumar, cofounder of Bangalore’s Workbench Projects say they spend most of their time explaining what a makerspace is. Maker’s Asylum calls themselves a community makerspace; where they focus on “hands-on learning and creative problem solving”. Workbench Projects, a registered fab lab in Bangalore promise to get that project “out of your head and into the world”.

Mentor Ankit Daftery is an independent maker and interaction designer who runs a company called Daf Labs in Bangalore

The concept of a makerspace comes from the hackerspace which started out as a European term for programmers who would gather and work together. And hence, both show similarities in ethics such as tendencies to opt for open source and community sharing.

Soon, US visitors returned home to emulate such events and organised hacks on their own. While it did start off predominantly with programmers, the communities soon moved on to working on circuit boards and real hardware to function in tandem with software. This shift from software to hardware is the crucial difference between hacker and maker spaces. It was a culmination of many things; the timing being most crucial. After the advent of the Internet, when consumers were satiated with giving real time feedback to brands, it was time to take things to the next level. Designers had had their feed with the software boom. And then digital manufacturing tools made an entrance. It connected designers to mini manufacturing units that could emulate the quality of the big factories owned by bigger brands. The consumer began to be the designer and the manufacturer as well. Digital files could be sent across the world and physical goods could be printed without further cost.

One of the first New York makerspaces, NYC Resistor is where MakerBot was born. MakerBot, the 3D Printer manufacturer is currently ripping apart the digital manufacturing industry. The many terms can get confusing but it’s important to remember that this is an unorganised community. Making is a way of life, not a cult you get sworn into. While most makerspaces around the world don’t have much to do with one another, it is the culture and sense of community that connects them. So though you may be associated briefly with a makerspace in Kolkata, if you were to visit one in Canada they would be curious to know what you built. It’s also a community that thrives on passion and goodwill. Think, activists who fight to preserve open spaces such as public parks, policies that encourage hands-on skill development so students can be job ready and hipsters who encourage productive use of leisure time. Well, makerspaces actually cater to all three. Add to that the lack of opportunity in a country that is rearing to move from the service industry to manufacturing, Make in India speak — and the supporters are more than happy to lend a hand.

Makerspaces approach learning as a byproduct of making. There is no curriculum or teacher but community members will help if and when you meet a roadblock

Be warned however; this is not a community that values talking as much as it does doing. This is more than obvious when speaking with Kumar and Chhabra who run the most popular makerspaces and base their establishments on their experience with contemporaries abroad.

For both, the lack of amenities while trying to prototype in India added fuel to setting up a similar enterprise in the country. Before setting up Maker’s Asylum, Chhabra was working with EyeNetra, a mobile eye diagnostic device manufacturer that was testing the product in rural Maharahstra. When he needed to make changes to improve the product, he was forced to send instructions back to the Boston office because he lacked the infrastructure to iterate locally.

Ask him what it takes to start a makerspace in India and he says, “the sky is falling”. That’s exactly what happened to Chhabra. One day in 2012, the ceiling of the rented office collapsed destroying all the furniture with it. The landlord offered to fix the ceiling but refused to pay for the damaged furniture, explains Chhabra. “So, we decided to build it ourselves,” he adds. He put out a message on social media explaining his situation and how he was looking for help. “On the first day, five people showed up. We spent all day building tables. I taught those who didn’t know. We had such a good time that when we were done with the tables, we just kept on going,” he narrates.

The Asylum’s first location was in the store room of Chhabra’s old office. Chhabra built his first table at Artisan’s Asylum a 40,000 sq ft makerspace in Massachusetts. He can afford to charge a nominal fee to members because corporates too are showing interest in tapping into the diverse community of makers who frequent the space. The origins of Workbench Projects is more clinical by comparison yet it reflects the same eagerness to get ideas off the drawing board. Cofounders of Workbench, Kumar and Anupama Prakash met while collaborating with an organisation that tried to encourage experiential learning of math and science in schools. “We got to collaborate on a very specific project to build a math activity centre called NumberNagar for primary and middle schoolers. It was a project that emphasised on user based experience design to make math teaching and learning highly multidisciplinary. The approach to the project demanded both aesthetic and functional design that called for several iterations during its execution,” explains Prakash.

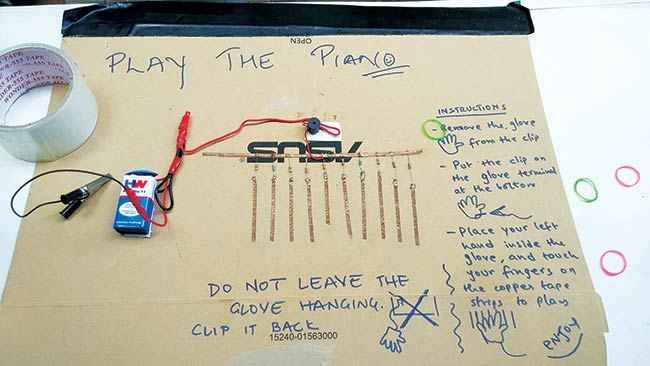

Abhijit Sinha’s Project DEFY creates learning spaces in rural areas. Here he displays a simple circuit piano made by children in a village on the outskirts of Bangalore

It was at this time that they realised that the city (Bangalore) did not have a space dedicated for prototyping. “One with ideas was either let loose to run pillar to post in search of different studio offerings rather than having a one-stop joint for idea exploration. The need was hence clearly defined” she adds.

Kumar came with the proposition to start a studio for idea exploration. They spent three months researching online, meeting with like-minded people, following which a white paper was articulated and shared with many international organisations from University professors to Fab Labbers. Fab Labs are licensed makerspaces, franchises if you may. The terminology has more to do with the way the space is run and managed than with the work that is done and leaves the space.

Fab Labs follow a charter of requirements regarding space, tools and curriculum laid down by founder Neil Gershenfeld at the Center for Bits and Atoms in MIT’s Media Lab around 2005. There is a core set of tools including basic electronics equipment, a lasercutter, a vinyl cutter, a CNC router, a CNC milling machine, etc to allow novice makers to make almost anything. Workbench Projects is a registered Fab Lab. “Within the first three months of its operations, we were invited by Bangalore Metro Rail Corporation (BMRCL) to activate one of their public spaces by conducting weekly workshops that we had initiated,” explains Prakash. Later, the city railway corporation offered them the opportunity to bid for one of their spaces under the Halasuru metro station where it currently operates from. As per the Fab Lab charter, Workbench is allowed to charge only a nominal rate from the community of makers.

Maker’s Asylum too charges members Rs 3,000 for a monthly membership. The token amount, says Chhabra, is just to ensure people are serious about safety, machines and making. In Delhi, Nuts and Boltz follows the same pricing for memberships. Founder Varun Heta who started the makerspace after experiencing the want of a community while teaching himself robotics.

The 3D printer is by far the biggest attraction of any makerspace. They cost upwards of Rs 1 lakh but locally made options come cheaper

How the space works is so; members sign up and the cost gives them access to the space, tools and community. With digital manufacturing tools, members must go through a training to ensure they know how it works and are aware of safety regulations. They are then free to use the tools on their own. Any product developed at the space using the tools is owned completely by the member. Of course, there are roadblocks. For individuals who visit makerspaces without wanting to get their hands dirty, it can take some unlearning of state education systems. If you are unwilling to pay a nominal charge to be able to learn and build things that would cost you ten times as much off the rack, well then perhaps being a maker isn’t for you. For start-ups it is a way to network with a community to crowdsource the next smart device. For venture capitalists, it’s easy pickings. For Workbench to have made headway with the government bodies that deal with innovation and skill development is a huge milestone for the movement.

| List of maker spaces in India | |

|---|---|

| Fab Lab- Startup Village, Kochi. | E4D Banjarapalya Bangalore. |

| Collab House, Hyderabad. | Workbench Projects, Bangalore. |

| Riidl Centre, Mumbai | Fab Lab-Technopark, Trivandrum. |

| Vigyan Ashram, Pune. | Makerloft, Kolkata. |

| IoT Labs, Bangalore. | Makers Asylum, Mumbai and Delhi. |

| Curiosity Gym, Mumbai. | Potential Labs, Hyderabad. |

| Meerut MakerSpace, Meerut. | National Innovation Foundation, Ahmedabad. |

| Jmoon labs, Delhi. | |

What is the future of makerspace? Well, it depends whom you ask. For hobbyists, it’s a place to play. Hardware entrepreneurs look at it as a way to iterate without bearing the heavy costs at the start of their journey. Corporates too are taking keen interest. They see it as an easy to reach pool of users of technology, tinkerer of goods and maker of future products to hit the market all wrapped into one.

Yolande Dmello

Yolande is a journalist by profession and a dreamer by choice. She’s worked with dailes such as Times of India, Mumbai Mirror, DNA and MiD DAY during a 5-year stint. In her free time, she likes to rhyme about killer robots and dance with her eyes closed. View Full Profile